By Anne Morrissy | Photography provided by Bridge Payne, Anne Morrissy, Martha Cucco, and Holly Leitner

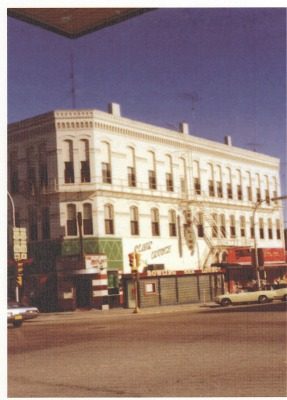

In 1955, a Lake Geneva bachelor named George Lazzaroni (“dapper and well-traveled,” according to a newspaper article of the era) became concerned about the lack of structured, wholesome activities available to young people in Lake Geneva, and he developed an idea to solve the problem. Lazzaroni and his siblings owned the imposing commercial building at the corner of Main and Broad streets in Lake Geneva that we now know as the Landmark Center. At the time, the building was the Hotel Clair, and in the basement the Lazzaroni family operated a popular bowling alley called the Clair Lanes. To occupy the young people of Lake Geneva, they decided to organize a youth bowling league.

George Lazzaroni may have been inspired to start the league remembering his own days as a young man in Lake Geneva. According to at least one local history, the basement bowling alley may have gotten its start during Prohibition when George Lazzaroni and his brother Eddie, both still teenagers, installed a handful of pool tables and the first two bowling lanes under their father’s ice cream parlor and confectionery. Patrons accessed the basement entertainments via the exterior staircase built into the sidewalk on Broad Street, and a new business was born.

RIGHT UP THEIR ALLEY

The official opening of the basement bowling alley and small adjacent tavern that would become known as the Clair Lanes dates to 1933, when the 21st Amendment repealed Prohibition and created new business opportunities. The Lazzaronis discovered it was a fantastic time to own a bowling alley. Bowling proved to be a well-loved Lake Geneva pastime in the 1930s, mirroring the sport’s popularity around the country. Throughout the 1930s and even past the end of WWII, bowling was the most popular participation sport in the country.

In a pre-television world, joining a bowling league provided Americans affordable entertainment and a weekly evening of socializing. Bowling was particularly popular in the Midwest, and it attracted a relatively high percentage of women compared to other sports of the era. In 1939, a tournament for women bowlers in Chicago boasted more than 1,000 teams from across the country. The Clair Lanes hosted nightly leagues for both men and women; Thursday night Ladies’ League was especially busy.

Bowling alleys of this era, including the Clair Lanes, featured hand-set pins tended by teenage “pin boys” who hovered behind the scenes waiting to reset the lane after each player’s turn, frequently risking injury to fingers, shins and ribs and getting paid a few pennies per game. In the 1950s, stricter child labor laws and the introduction of automatic pin-setting machines made the pin boys obsolete, but the sport continued to attract new devotees, as evidenced by George Lazzaroni’s interest in organizing a youth league during that era. By the 1960s, bowling was such a phenomenon nationally that professional bowlers could make twice as much as NFL stars. In the middle of the 20th century, bowling was big business.

THE METROPOLITAN BLOCK

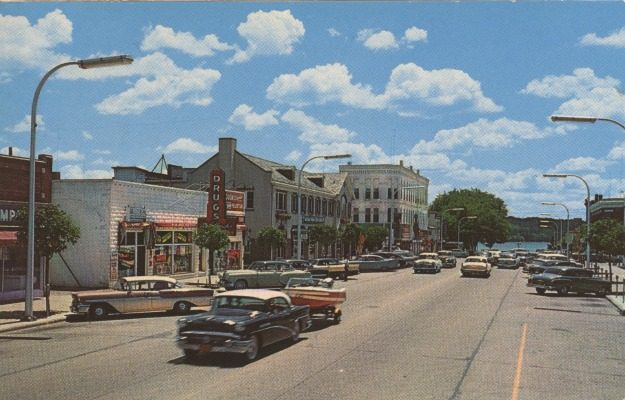

The building that housed the Clair Lanes had been a Lake Geneva fixture for many years before the Lazzaronis opened the bowling alley in its basement. In 1874, just three years after the Great Chicago Fire made Lake Geneva a newly popular summer resort, local businessmen and investors D.S. Allen and H.H. Curtis funded the construction of the impressive, Italianate Cream City brick building they originally called The Metropolitan Block. It was one of the first significant brick buildings in downtown Lake Geneva, where brick had only just begun to replace older frame buildings.

Allen and Curtis hired the famous Chicago architect William LeBaron Jenney to design the Metropolitan Block. Jenney came to be known as the father of the original “Chicago School” of architecture because his firm hired and trained so many luminaries of that movement. At the time of The Metropolitan Block commission in Lake Geneva, one of the architects working in his firm was Louis Sullivan, who went on to design many iconic Chicago buildings and mentored several of the architects who would eventually form the Prairie School, including Frank Lloyd Wright. (Wright’s Geneva Hotel would be built less than 100 yards away from The Metropolitan Block in 1911.)

Jenney’s original design for the Lake Geneva commission combined first-level storefronts with upper-level office suites and meeting halls. The earliest businesses to occupy the building included investor Curtis’s drugstore (which became Arnold’s Drugstore a few years later), the H.M. Hicks Harness Shop, Frank Valentine’s New Cash Metropolitan Store for groceries, John Carlton’s barber shop, the Geneva Lake Herald offices and a doctor’s practice. The second floor also contained a ticket office and lecture room which seated 150 people. The third floor was taken up by the Metropolitan Hall, a large meeting space possibly intended for use by local civic groups and fraternal organizations.

THE LAZZARONI FAMILY

George Lazzaroni’s interest in youth culture in the 1950s continued a tradition his family had started four decades earlier when they first took over the Arnold’s Drugstore space in the Metropolitan Block and opened the Lake View Ice Cream Parlor and Confectionery. Lazzaroni’s parents, Max and Mary, left their native Italy in 1893, settling in Chicago. Sometime between 1902 and 1906, they packed their belongings and their growing family into a horse-drawn buggy and headed to Lake Geneva, a journey that took them three days.

Max Lazzaroni’s story follows a classic American script. When they first arrived in Lake Geneva, the family operated a fruit stand in downtown Lake Geneva. In 1910, Max opened the ice cream parlor, and eight years later he had proved such a successful businessman that he bought the Metropolitan Block building and opened a lunch room in part of the Broad Street frontage. During this era, Wright’s Geneva Hotel was bringing more visitors to downtown Lake Geneva, so it’s likely that Max Lazzaroni opened the lunch room to capitalize on the increased tourism. In a few short years, he had gone from fruit seller to prominent local business owner and real estate investor.

HOTEL CLAIR

Alongside his father, George Lazzaroni must have observed that tourism was good business in Lake Geneva. In 1937 after inheriting the Metropolitan Building following their father’s death, Lazzaroni and his siblings remodeled the ice cream parlor into the Clair Lounge, a sleek art deco space with a curved bar and high-backed banquette booths, and converted the second and third floor into hotel rooms. They christened it the Hotel Clair. According to Lake Geneva resident and Lazzaroni family descendant Sean Payne, George Lazzaroni and his siblings lived in individual rooms at the Hotel Clair, sharing a common kitchen area on an upper floor.

During the hotel conversion, the Clair Lanes remained relatively unchanged. George Lazzaroni’s sisters Genevieve and Alma, both avid bowlers, managed the dayto-day operations. In 1945, they rebuilt the external stairway to the bowling alley and enclosed it, part of an exterior cosmetic update to the building that also included reshaping the windows and painting of some of the cream-colored bricks on the first level. To promote their business, they added a large and distinctive sign that protruded from the Broad Street side of the building: a giant bowling pin.

Further updates and additions enhanced the Hotel Clair, the Clair Lounge and the Lazzaroni commissioned the local photo print studio owned by Vern and Alice Hackett to create six large-format photo prints of Lake Geneva scenes using new technology the Hacketts had pioneered in printing and hand-painting photographs onto translucent surfaces. (Five of the iconic, backlit Lake Geneva “photo signs” can be found at nearby Mars Resort today, while one is in the Geneva Lake Museum.) The youth league that George Lazzaroni started began to draw a new generation to the Hotel Clair building.

Sean Payne’s sister Bridget grew up working in the bowling alley in the 1960s and 1970s. She and her siblings walked to the Clair Lanes from their home in Lake Geneva almost every day. “We would shine the shoes, fill the pop machines, fill the candy machines, whatever needed to be done,” she remembers. “That’s how we learned to work.”

FROM A BOWLING ALLEY TO A DUNGEON

By the 1970s, although bowling remained a popular American pastime, the Clair Lanes faced increasing competition from newer bowling alleys in the area. Similarly, the Hotel Clair began to look dated when compared to the new motor hotels that popped up on Motel Row in the 1950s or the gleaming new resorts like the Playboy Club that opened in Lake Geneva in the 1960s.

When George Lazzaroni passed away in 1978, the Hotel Clair had not been significantly updated in a long time, and the building went up for sale. Gary Gygax, a Lake Geneva entrepreneur and game developer, had just begun to see monumental success with his latest creation, an innovative role-playing game called Dungeons & Dragons. Gygax and his partners formed a company called TSR Inc., and bought the Hotel Clair to use as its headquarters.

They de-converted the Clair Lounge back into a storefront and opened the Dungeon Hobby Shop, where they sold games, supplements and other retail merchandise related to the Dungeons & Dragons phenomenon. They renovated the second and third floor of the building into offices, and tore out the bowling alley to use as a shipping department.

However, Dungeons & Dragons experienced such a meteoric rise in popularity (the New York Times declared it the “great game of the ’80s” ) that TSR Inc., quickly outgrew the Hotel Clair space and moved their headquarters to a larger building on Sheridan Springs Road. By 1984, more than 100 years after it was first built, the building originally known as the Metropolitan Block sat empty for the first time.

REBIRTH OF A LANDMARK

In 1986, local contractor Karl Otzen undertook a significant restoration and rehabilitation of the Metropolitan Block. Most notably, he rebuilt the interior to match Jenney’s original building plans as closely as possible. He also replaced the impressive interior stairs and updated all of the mechanical, electrical and plumbing systems. On the exterior, he re-opened

windows that had been bricked over, carefully removed the paint from the brick, and rebuilt large sections of the masonry to repair structural damage. For the first time in decades, the Metropolitan Block once again closely resembled its original 1874 look.

In 1990, the National Park Service approved an application to place the Metropolitan Block on the National Register of Historic Places. The building has been known as the Landmark Center since that time. Several shops and businesses, including Kilwins Chocolates, occupy the Landmark Center today, an endearing nod to the days when the Lazzaronis sold ice cream and confections from the same spot.

The building at the corner of Main and Broad streets has remained a recognizable icon of downtown Lake Geneva since it was first built 143 years ago. Though it has been re-purposed several times, the building’s enduring visual appeal is a testament to its famous architect, William LeBaron Jenney. But its place in the hearts of many Lake Geneva residents and visitors of the 1930s through the 1970s can be traced not to its elegant façade but to the basement, where for many decades, people gathered together for a little fun and friendly competition, bowling balls in hand.

Special Memories at Hotel Clair

Lake Geneva resident Bridget Payne grew up working in her family’s business, the Hotel Clair, during the late 1950s and into the 1960s and 1970s. It was her uncle George and his siblings who transformed the Metropolitan Building after their father (Bridget’s grandfather) passed away, converting the ice cream parlor into a lounge and adding hotel rooms to the second and third floors.

Bridget shares some of her memories of the bowling alley, lounge, hotel and the people who frequented this popular hot spot in downtown Lake Geneva.

“I was between 4 and 5 years old when I started bowling. As I grew older, I learned this was the place to be in Lake Geneva to bowl, to see live entertainment and to meet up with friends.”

“When I was a little girl, the Clair Lanes didn’t have automatic pin-setters. There was a bench over the pins and boys would jump down off the bench to reset the pins, which could be quite dangerous if you weren’t careful.”

“As kids, we did any job we were asked to do. Sometimes we cleaned bowling shoes for 5 cents a pair. That added up when you cleaned 20-25 pairs in a night!”

“Seems like everyone belonged to a bowling league back then or that everyone bowled. Tuesday and Wednesday nights was men’s league; Thursday was ladies’ league; Friday and Sunday they had mixed couples’ leagues and Saturday was open bowling. “My great-grandmother, Marianna Lazzaroni watched the bowling leagues every night and while watching she would knit. I swear she would knit a sweater every night — her hands would fly!”

“In the mid-60s they removed two bowling lanes and added five pool tables. The racks of balls were kept behind a counter and we’d rent those for $1.50 an hour.”

“There was always live entertainment — bands and even performers and comedians in the lounge on weekends. And some of the performer who played at The Riviera, like Louis Armstrong, would stay at Hotel Clair because it was less expensive than the Geneva Hotel down the block.”

“The rooms at the Hotel Clair were basic — only a couple of them had private baths, but that was just more common at that time.”