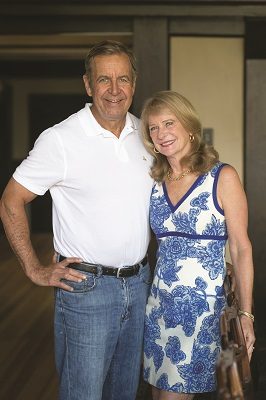

By Anne Morrissy | Photography By Shanna Wolf

In the middle of the night on September 2, 1978, during the height of Labor Day weekend on Delavan Lake, an unidentified arsonist crept into an elegant, historic boathouse on the south shore of the lake and set the structure ablaze. By the time the homeowners Burr and Peg Robbins woke up in the main house at 4:30 a.m., the fire was too far gone — the entire boathouse was eventually lost, with only the fieldstone retaining wall surviving to commemorate its existence. This was the fifth such case of arson on Delavan Lake that summer. But the loss of this structure was arguably the saddest, at least from an architectural and historical perspective. The boathouse, like the rest of the buildings on the property then known as Robbinswood, had been designed at the turn of the 20th century by none other than famed architect Frank Lloyd Wright. At the time of its destruction, the boathouse, along with three other Frank Lloyd Wright- designed buildings on the property, was listed on the National Register of Historic Places.

John and Susan Major bought the property in 1994, and made it their goal to restore these historic buildings to as close to their original design as possible. According to John, each year they undertake at least one project related to maintaining and restoring Wright’s vision. So in the early 2000s, using Wright’s original blueprints, the Majors rebuilt the boathouse exactly as it had been before succumbing to fire that fateful night in 1978. Almost 25 years later, Wright’s vision for the estate was once again complete.

FRANK LLOYD WRIGHT AND PENWERN

At the turn of the last century, Delavan Lake was gaining ever greater appeal as a summer getaway spot. Recognizing the increasing popularity of the area, a hardware store owner, real estate developer and acquaintance of Frank Lloyd Wright’s named Henry H. Wallis bought land on the lakefront with the intention of subdividing and selling off the lots. Initially keeping one lot for himself, Wallis commissioned a home from Wright and also recommended Wright’s architectural services to clients as he sold off the remaining lots. Wright would ultimately design five estates on Delavan Lake.

In 1900, a well-traveled bachelor named Frederick Bennett Jones bought the lot next to Wallis’s and commissioned Wright to design all of the buildings on the property. Wright designed four buildings in all for Jones: the main house, a winterized gatehouse and water tower, the boathouse and the stables/garage. Before delivering the plans to Jones, Wright named the property Penwern, perhaps in a clever nod to his own grandmother, whose surname was also Jones and who had grown up on a Welsh estate known as Penwern.

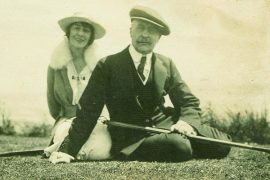

FRED B. JONES

By the time he commissioned Wright to design Penwern, Fred B. Jones was managing director at the Adams & Westlake company in Chicago, which manufactured light hardware for many rail and streetcar companies as well as bicycles, cameras, kitchenware and brass beds. At Delavan Lake, Jones was an avid sportsman and card player who threw large parties and frequently hosted weekend guests. In addition to his active philanthropy, Jones served as the President of the Delavan Lake Yacht Club for at least two years, leading the effort to build a new clubhouse (also designed by Frank Lloyd Wright), which was built in 1904. (That clubhouse was demolished in 1916 when the club merged with the new golf club and a new clubhouse was built.)

Ultimately, Jones’s lifestyle and hobbies determined Frank Lloyd Wright’s design for Penwern. The main lodge faces the lake and features an impressive terraced patio and porches ideal for entertaining. An arched porte cochere and an open-air walkway connect the main lodge to a smaller tower annex where Jones hosted men’s-only card games. According to Susan Major’s research, this served the twin purposes of providing the men with a certain amount of privacy and keeping the thick cigar smoke from bothering other house guests.

The main lodge features soaring ceiling heights (good for catching the lake breeze,) an impressive billiards room, a massive living room and a banquet-sized dining room, as well as five good-sized bedrooms, all ideal for entertaining large groups. To protect valuables in the off season, Wright even designed a large, two-story-tall “safe room” that was hidden behind an imposing built-in liquor cabinet. And to make sure that Jones would never be thirsty, he added three copper faucets throughout the home intended solely to dispense water for his drink of choice: whiskey and water.

True to his style, Wright designed all of the buildings at Penwern in harmony both with each other and with the land on which they were built. According to architectural experts, Penwern represents an early iteration of Wright’s “Prairie Style,” but adapted to the wooded terrain around the lake. The main home is distinguished by strong horizontal lines (courtesy of the board-and-batten siding) as well as the incorporation of native fieldstone extending directly from the earth. Inside, Wright created a signature open-plan design, varying the floor levels and ceiling heights to define the spaces within. He included several touches that proved to be a hallmark of his style: a massive arched brick fireplace in the living room, leaded glass windows, inglenooks (built-in benches beside the fireplaces,) and several items of built-in furniture, including a sizeable buffet in the dining room.

ALL BUILDINGS ARTISTICALLY DESIGNED AND SITED

Wright devoted just as much care and attention to the siting and design of the property’s outbuildings. The gatehouse on South Shore Drive was the most significant of these — it was constructed in 1903 and housed Jones’s gardener/ caretaker and his family. The gatehouse connects via an archway to the cedar barrel water tower, which once served as a water source for an attached greenhouse. (In addition to his many other hobbies, Jones was an avid rose gardener.) Initially the gatehouse was the only building on the property that was winterized, so that the caretakers could remain year-round. But, according to John Major, about 10 years later, Jones added a basement and installed a coal furnace so he could keep the main house open later into the fall.

The Penwern boathouse echoes the architectural design of the main lodge, and provided storage space for Jones’s “gasoline launch,” a 25-foot-long excursion boat. The upper floor featured an open-air deck with a roof overhead, an ideal spot for Jones’s annual July 4th party (a tradition the Majors have resurrected). Similar to the main house, the boathouse’s foundation and retaining wall were built using native fieldstone, and Susan Major points out that Wright scholars have identified an early Asian influence in the boathouse’s roofline. “It’s amazing how Wright designed the property so that the view [from the main house] isn’t blocked by the boathouse,” she marvels.

The stables feature the familiar peaked gables of the other buildings, and initially housed Jones’s horses and carriages. However, as John Major points out, Penwern was built during a time of great technological change, and it’s likely the stalls were soon filled with automobiles instead of horses. To ensure that Jones would also have enough refrigeration, Wright designed one section of the stables for use as an icehouse to store blocks of ice harvested from Delavan Lake in the winter.

At the height of Jones’ ownership, the Penwern property consisted of 10 acres, including a picnic grove on the east side of the property. When Jones passed away in 1933, the property sat empty while a group of cousins challenged his will. Ultimately, the Robbinses bought Penwern in 1938 and owned it for almost 50 years, making additions and alterations during that time to suit their needs. By the time the Majors bought the house in 1994, the main house and gatehouse had separate owners, but the Majors were able to reunite the properties in 2001.

PASSION PROJECT AND DREAM HOME

“We weren’t necessarily looking for a specific architect,” explains John Major when asked how they came to buy Penwern. “I’m from the East Coast, and honestly when we first looked at the house, Frank Lloyd Wright wasn’t even in my vocabulary yet.” But the Majors, who now split their time between Delavan and Rancho Santa Fe, California, had also owned a vintage farmhouse in Barrington Hills, Illinois, and knew they were up to the restoration challenge that Penwern presented. The first projects they tackled after buying the home included reinforcing the support of the house, straightening the floors, adding insulation and installing new furnaces.

Over the years, the Majors became avid Frank Lloyd Wright historians and researchers of Penwern, ultimately acquiring 17 of the original Wright-penned drawings for the property. Over the past 20 years, they have worked tirelessly to restore the home as close to its original design as possible. Today, John says, the home occupies the footprint of Wright’s design and almost all of the rooms have been restored to their near original states. “The only real liberty we’ve taken is in the kitchen,” he explains. As Wright designed it, the kitchen consisted of three small rooms to accommodate servants and the various tasks associated with food preparation at the turn of the 20th century. The Majors combined all of the rooms into one – the result is a large, open-plan kitchen centered around an enviable island, perfectly aligned with modern needs and tastes, and yet still carrying Wright’s design influence.

The Majors have also converted bedroom closets into additional bathrooms (Wright’s original plans included only one bathroom for the house) and enclosed a screened porch on the back of the home, which created a lofted office space as well.

Elsewhere on the property, in addition to rebuilding the boat house, the Majors have also completed several projects, including restoring and rebuilding the front of the garage to Wright’s original vision. With each project, the Majors have drawn on extensive research and hired diligent contractors and experts to ensure that each building maintains its historical integrity. In 2005, their dedication to Penwern earned them the Wright Spirit Award from the Frank Lloyd Wright Building Conservancy.

Though the Majors may not have realized it when they first looked at the property more than 20 years ago, buying Penwern set them on a journey that is still unfolding. “I love history,” says Susan, “and I consider myself the steward of the house.” When asked to choose his favorite room in Penwern, John is stumped. “It’s hard to choose a favorite,” he says. “Because of the quality of the design, there are lots of great spaces in this house.”

A forthcoming book about Penwern will be published by the Wisconsin Historical Society Press in the fall of 2018. For more information about the history of the estate and the Majors’ restoration of it, visit penwern.com.