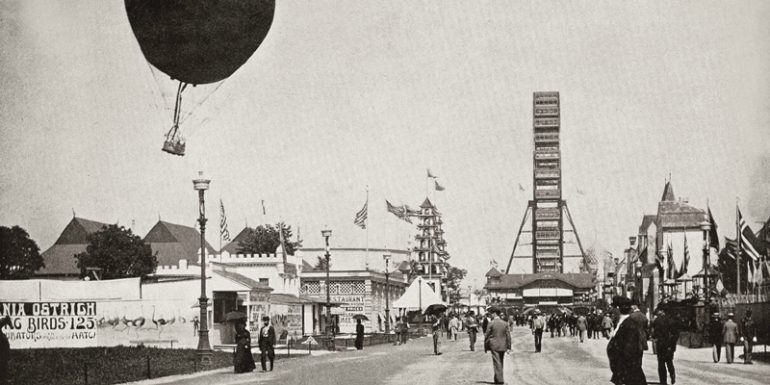

On May 1, 1893, the World’s Columbian Exposition opened its gates to the public to celebrate the 400th anniversary of Christopher Columbus’ voyage to America. During the fair’s six-month run more than 20 million visitors flocked to the 600-acre site along Chicago’s lakefront, now a part of Jackson Park. Those strolling through the numerous new buildings of Classical design viewed a variety of exhibits.

Nearly 50 foreign countries and 43 states and territories were represented in Chicago, plus American pavilions showcased the country’s diverse history, food and culture.

The impact of the event inspired lives both near and far, shaping industry and architecture, international relations and domestic lifestyles.

Chicago and Lake Geneva have always been inextricably entwined, and when the gates of the highly celebrated and highly influential World’s Columbian Exposition closed forever, parts of it would make their way to southern Wisconsin. The following are several of the known structures to arrive in Lake Geneva in the wake of the famed World’s Fair.

CEYLON COURTS

In February of 1893 a party of 53 Singhalese natives arrived in Chicago on a bitterly cold winter day with 300 tons of material and immediately set to work bringing a part of their ancient island’s history to the World’s Fair. The people of Ceylon and Great Britain, who had colonized the island of Ceylon in 1798, now Sri Lanka, created Ceylon Courts. Not only was the island’s major tea industry of great importance to England and its other colonies, but the Columbian Exposition was an excellent opportunity for Great Britain to introduce this export (as well as nutmeg, ebony, cinnamon and mace) — and their interests — to Americans.

The buildings of Ceylon Courts replicated ancient ruins discovered on the island in the early 1800s and were built with native materials, such as teak and mahogany, and dyed to match traditional colors. The 162-foot-long Singhalese Temple (known as the Principal Court), the main building of the exhibit, was comprised of a central octagonal hall 50 feet wide with two wings on either side, and made from some 20,000 cubic feet of timber felled for this very purpose. The three-tiered building’s octagonal central hall had 24 carved pillars, 32 decorative ceiling panels, as well as hand-painted interior walls and ornamental floors — all of which beautifully illustrated Ceylon’s history, art and religion.

An octagonal-shaped Tea Room, about 35 feet in diameter, stood over the central hall (and above this, a traditional kola, or temple spire). Although simpler in its ornamentation than the structure below it, the Tea Room was of similar design and equally impressive with its ornamental screens and carved balustrades, light and dark native woods, wall hangings and windows offering an extraordinary view of the Exposition grounds.

Mrs. Anna Chandler (wife of real estate magnate Frank R. Chandler) was so fascinated by the exhibit that she eventually talked her husband into purchasing the 18,706-square-foot Principal Court and having it transported to land above Geneva Lake’s eastern shores, overlooking Button’s Bay, in 1895. Henry Lord Gay supervised the reconstruction of the temple and also designed an upper level addition.

When John and Mary Mitchell purchased the estate in 1901, they increased the distinctive Singhalese structure to 23 rooms.

YERKES TELESCOPE

The world’s largest telescope was on exhibit for Chicago fair-goers in the grand Manufactures Building, which, at nearly a third of a mile long, was said to be the biggest building ever created by man. The cutting-edge telescope stood in the center of the building’s great aisle and was electronically pivoted on two axles so that visitors could watch in amazement as the telescope operator pointed the massive device from one end of the sky to the other. The telescope’s main lens, 40 inches in diameter, was not actually in the tube at the fair, as it had not yet been completed. However, the scene was still an impressive one. The mounting stood 43 feet high and weighed 50 tons; while the telescope tube weighed 6 tons and was 60 feet long.

In November of 1893 the colossal Manufactures Building caught fire. The University of Chicago’s president, William Rainey Harper, acted quickly, gathering enough men to carry the telescope out of danger. Although several pieces of the mounting were lost, the telescope was undamaged. Eventually the telescope would be pieced together and installed at the University of Chicago’s Yerkes Observatory in Williams Bay, which would soon be known globally as the leader in modern astrophysics.

DANISH PAVILION

The Danish Pavilion was Denmark’s contribution to the World’s Fair. The pavilion, built in the 1880s, had a guesthouse and portions of a main house, which included a solid hand-carved staircase and inlaid parquet floors. When the fair was over, the pavilion became the core of what is now the French Country Inn on Lake Como.

THE IDAHO BUILDING

Walk along the shores of Big Foot Beach State Park and you’ll be trampling all over Celia Whipple Wallace’s dreams. Once upon a time, in 1896, this wealthy Chicago widow built a rustic log cabin here — a peculiar act for a well-to-do woman often reported to be dripping in diamonds. So famous was her reputation for expensive jewelry, members of the Chicago press dubbed her “The Diamond Queen.” So why was it that the Diamond Queen wanted to build a log cabin on Geneva Lake? Well, the truth is, this wasn’t just any old cabin. It was the handsome, three-story Idaho Building from the Columbian Exposition, one of the most popular exhibits at the fair that drew an estimated 18 million people to its doors.

The Idaho Building was truly a sight to be seen. Created entirely out of native materials, the large structure had lava and basaltic rock at its base, aged cedar timbers above, expansive lower and upper balconies, and a shake roof held in place with heavy rocks. The charming log home’s arched stone entrance opened into a large room, at the end of which was a stick fireplace with a log mantel. The second-floor windows were glazed with mica, and the rooms, decorated with mining scenes, were divided between men and women. The interior boasted a fireplace made with lava rock native to Idaho and accented with andirons construction of bear traps and fish spears. Native American accouterments were incorporated throughout the décor.

The furnishings were said to be a major precursor of the Arts and Crafts movement.

After regularly summering in Lake Geneva as a resident of the Whiting House, the wealthy widow purchased an empty tract of bog land, then known as Sand Beach, on the south end of Button’s Bay. Rumor had it that initial plans for a residence were drawn up by Henry Lord Gay, but never acted upon. However, in 1895, Wallace finally had her summer residence, purchasing the Idaho Building and ordering it to be reassembled on her lowland in Lake Geneva.

Reports say that at some point Wallace intended the Idaho Lodge to be a summer retreat for orphaned boys. Indeed, she had a track record for caring for those less fortunate. But orphaned boys never took up summer residence in the Idaho Building, nor did Wallace, who continued to summer at Lake Geneva’s hotels. Long known for her eccentricities, Wallace found herself with mounting debt and ultimately sold the cabin for $15,000.

The Idaho Building was again put up for sale, but there were no takers and the structure quickly fell into disrepair.

Groups reported to have occupied it during its short life on Geneva Lake included road crews, student artists and “an unauthorized band of gypsies.” In 1911 the dismantling process began, using some of its enormous cedar logs as planks for the new pier on Broad Street. By 1916 all that was left of Idaho Lodge was its stone foundation and a chimney.

THE NORWAY BUILDING

The Norway Building was constructed of pine in Trondheim, Norway, and shipped to the exposition in sections, then re-assembled by Norwegian workers. Twenty-five by 60 feet, the building was a replica of a 12th century “Stavkirke,” a Norwegian church with architectural features that included a high-peaked, gabled roof boasting fire breathing dragons. Inside, it also featured massive beams with carved faces of pagan Norwegian kings and queens.

After the fair, its new owner, Cornelius Kingsley Garrison Billings (a board member of the Columbian Exposition), moved the building to his Green Gables estate. The enchanting structure was installed near the lake — not to be used as a residence, but as a delight for the eyes of excursion boat passengers. When William H. Mitchell (father of John Mitchell of Ceylon Court) purchased the estate in 1907, the Scandinavian structure remained a unique part of lakeside living, as it did with the estate’s next owner, William Wrigley Jr., until 1935, when the building was donated and moved to Little Norway in Mount Horeb, Wisconsin, where it remains. The Norway Building is said to be one of the last remaining buildings from the World’s Fair still intact today. It was listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1998.

Editors Note:

A reader contacted us regarding the stave church mentioned in “The Norway Building” section of this article and indicated it had “been dedicated back to where it was built.” After some research, we learned the church, which was once located on Geneva Lake and donated to Little Norway near Mount Horeb, Wisconsin, has indeed been returned to Norway where it was constructed prior to its shipment to Chicago for the World’s Columbian Exposition. This article was reprinted from Geneva Lake Stories from the Shore, published prior to the church’s removal from Wisconsin. We apologize for this omission.