By Sarah T. Lahey

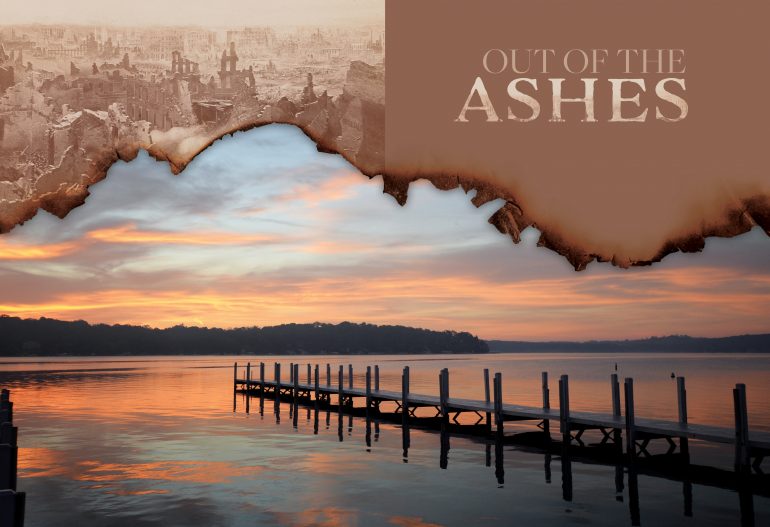

On the night of Oct. 9, 1871, Ada Rumsey (daughter of former Chicago mayor Julian Rumsey) stood alongside her mother as she watched red-hot flames reach toward her childhood home on Chicago’s Huron Street. The fire would soon engulf the entire property, and the Rumsey family would be forced to flee. Carrying only a few valuables — family portraits, heirloom silver, insurance papers — they eventually made their way to the Chicago & Northwestern Railroad station. With the fire still raging, the destination was clear: Lake Geneva.

The Rumsey family was one of many who made their way to Lake Geneva in the aftermath of the Great Chicago Fire of 1871. The Lake Geneva extension of the Chicago & Northwestern train line had been completed only a few months earlier. For families with financial means, the Wisconsin lake town became the perfect place to wait out the worst of the fire’s damage. Many of those families would go on to establish summer residences around the lake. Today, 150 years later, the influence these wealthy “resorters” exerted on the Lake Geneva area in the aftermath of the fire lingers still, from the opulent lake homes they inspired, to the charitable organizations they founded, to the area’s continued status as one of the premier resort towns in the Midwest.

A CITY ON FIRE

The Great Chicago Fire raged for three days from Oct. 8-11, 1871. It had been a hot, dry summer — Chicago received only 1.5 inches of rain from July to October. These conditions, coupled with high winds, created the perfect environment for the powerful fire, in a city made almost entirely of wooden buildings. The fire eventually become so powerful that it leapt the Chicago River not once, but twice, destroying any hope Chicagoans had of protecting the city.

As Ada Rumsey recalled in her memoir:

“The sky kept getting redder and redder; the wind, already high, was increasing with the heat, and huge burning cinders were settling in every direction… refugees loaded with goods were going north by our house; and altogether the circumstances were terrifying.”

As the fire continued to move from the south to the north side, more and more families were forced to evacuate their homes. When the fire finally burned itself out on the third day, the stunned city took stock of what was left: fire had killed more than 300 people, damaged 2,000 acres of property and left one-third of Chicagoans without homes. The final tally of destruction: roughly 17,000 buildings and an estimated $200 million lost. To many, amid all of this chaos, Lake Geneva stood like a beacon of hope.

A SAFE HAVEN

At the time of the Chicago Fire, there was just one summer estate on the lake — Maple Lawn, belonging to Chicagoan Shelton Sturges, heir to a large grain elevator fortune. He had purchased the Montague Farm in 1870 and transformed the modest property, building a mansion with extensive grounds. Following its completion, Sturges made it his life’s mission to recruit friends and family to join him at the lake.

In the summer of 1871, just prior to the fire, Sturges had moved his family into the main house at Maple Lawn, while his brother Buckingham took over the property’s original Montague farmhouse. Their brother George and George’s Chicago neighbor, Julian Rumsey, rented rooms at a boarding house in town. Thus, the very first “society season” at the lake included the Sturges and Rumsey families.

The Rumseys had only been back in the city for a few weeks when the fire destroyed their home, so it is no surprise that they viewed Lake Geneva as their logical refuge. According to Ada’s memoirs, they arrived with no change of clothing, so the townspeople sewed them new clothes. The next year, the Rumseys began building their own Lake Geneva summer estate, called Shadow Hill, which they completed even before they rebuilt their Chicago home.

THE RUSTIC VILLAGE OF GENEVA

The Geneva Lake that greeted these refugees from the Chicago Fire was not yet an elite summer destination. It was an undeveloped, forested, pristine lake more suited to rustic camping, with a small village on the east end of the lake, a group of houses near Williams Bay and another small settlement at the lake’s west end. A little more than three decades earlier, after the U.S. government removed the Potawatomi Indians in 1836, the first white settlers had begun to arrive in the area – mostly tradesmen and farmers. By 1838, the tiny Village of Geneva boasted two small hotels. In 1844, the village was officially incorporated and a decade later, the first newspaper was published.

Throughout the 1850s, the new settlers continued to build homes, schools and churches. However, the shoreline of the lake remained mostly undeveloped; farmers were more interested in flat, tillable land. As Mary Burns Gage and Ann Wolfmeyer have suggested in their book “Newport of the West,” the lakeshore in 1870 presented a quiet scene: “mile after mile of dense woods broken only by a small cluster of homes marking Williams Bay, and the village of Geneva… with a population of barely over 1,000.”

There were no paved roads around the lake, only a small number of buildings on the shoreline and few tourists, though a handful of intrepid campers made the trek to the lake for swimming, fishing and relaxation, a trend that would only increase in the years following the fire.

CAMPS BEFORE COUNTRY CLUBS

It’s important to note that despite his relatively early arrival, Sturges did not discover a lake entirely devoid of tourists. Before the millionaires arrived, Geneva Lake played host to an active camp scene. As early as the 1860s, numerous groups began traveling to Geneva Lake to camp and fish. Finding they enjoyed their summer nights spent on the shores of the lake in tents, these groups began buying plots of land to establish more permanent campgrounds. Early examples include Camp Collie (now Conference Point Camp), the Lakeside Park Club of Elgin (now Elgin Club), Belvidere Camp (now Belvidere Park) and Harvard Camp (now Harvard Club).

These communities began as sites for modest tent camping — initially no one was looking to build an expensive summer home. Even the relatively glamorous Buena Vista community in Fontana (which at one point contained two elaborate fountains) began in 1875 as a rugged campsite called Porter’s Park. At Elgin Club, a small group of fishermen happily spent their summer nights camping in tents until 1874, when they replaced their tents with cottages around a central dining house, a practice that was repeated at many of the camps over the years.

Even the large and well-known 19th century resort Kaye’s Park (now the South Shore Club) began in 1873 as a campground. Originally the site held one cottage for proprietor Arthur Kaye and his family, and tents for the guests. Over the next two decades, Kaye would transform the property into a glamorous resort with multiple lodging options, an elegant dining room, a racetrack, zoo and museum.

FAMOUS VISITORS

It’s hard to say exactly what changed the farming and camping community of Lake Geneva into a luxurious resort town. Was it the completion of the train line, bringing countless visitors from Chicago? Was it the Great Chicago Fire, which sent both rich and poor in search of lodgings, first temporary and then more permanent? Or was it Shelton Sturges, the first millionaire to build a mansion at the lake? It was likely a combination of all three — with a bit of help from celebrity visits.

In May 1872, the Lake Geneva Herald reported, “Our hotels receive guests almost every day and our streets are made more lively and agreeable by the presence of constantly increasing numbers of Chicago friends.” It was the summer after the Chicago Fire, and many visitors returned to the lake for fresh air and a change of scenery. In August, former First Lady Mary Todd Lincoln stayed at Colton’s Exchange, a Lake Geneva hotel, adding to the air of excitement.

The following summer saw a visit from another Civil War-era icon: General Philip Sheridan. He had taken command of Chicago in the weeks after the Great Fire, overseeing a period of martial law. Because of this, he achieved a level of local celebrity that made both tourists and locals excited to meet him. During his visit, Sheridan stayed in the private home of Dr. Philip Maxwell (today the Maxwell Mansion) and viewed a regatta held in his honor by the Lake Geneva Yacht Club. The Sheridan Cup race is still held annually.

THE “SARATOGA OF THE WEST”

Not far from Dr. Maxwell’s private home, the Whiting House Hotel opened its doors in 1873, offering the first luxury hotel accommodations at Geneva Lake. (The site today contains the Geneva Towers condominiums.) David T. Whiting built the 60-room hotel to “accommodate Chicago’s finest guests,” and it offered stunning lake views as well as a world-class ballroom. Beginning in 1875, visitors to the area would have seen the first Lady of the Lake, a double- decker steamer capable of carrying 200 passengers, docked not far from the Whiting House Hotel.

On rides aboard the Lady of the Lake, visitors would have enjoyed gossiping about the new mansions springing up on the shoreline. Following the Chicago Fire, several wealthy Chicagoans built estates around the lake, following in Sturges’ lead. The Rumsey family was one of them. Other early lakefront property owners included Allen C. Calkins, a former Chicago alderman who built a 10-room cottage called Oak Lodge on Geneva Bay in 1873, N.K. Fairbank who built Buttnernuts in 1874 (and then rebuilt it the following year after it burned to the ground), and George L. Dunlap, who built the Moorings on the site of today’s Stone Manor in 1875.

In August 1875, a “special correspondent” for the Chicago Tribune wrote an article on the transformation of Lake Geneva. The article described how “a staid, quiet little village has already been metamorphosed into a metropolitan resort.” The correspondent named the Sturges family as “pioneers” of this change and further dubbed Lake Geneva the “Saratoga of the West” after the popular resort town in upstate New York. Later, Lake Geneva would earn the nickname “Newport of the West,” in reference to the East Coast’s most elite summer resort area.

A TOWN TRANSFORMED

On April 29, 1874, Rumsey met with Calkins, Fairbank and Dunlap at the Whiting House Hotel to establish the Geneva Lake Yacht Club. They created the club’s bylaws, set rules for boat races and elected Fairbank the club’s first commodore. Here were some of Chicago’s top businessmen and political leaders, gathered at the newly built Lake Geneva hotel to determine how best to race their new yachts. This meeting, in many ways, marked the moment that the area transformed from a small farming community into a luxury resort, a transformation which had its beginnings in a massive conflagration.

Looking out at the flames approaching her home in 1871, Ada Rumsey could have had no way of envisioning the impact the devastating fire would have on the rural Wisconsin lake town where her family had just spent a relaxing summer. But in the aftermath of the tragedy, her family’s decision to make Lake Geneva their summer home, a decision echoed by many of the elite families of Chicago, would ultimately mold the area into the world-class resort town it remains to this day.