By Lisa M. Schmelz

History — literally his story — has done a far better job preserving the lives and contributions of men than it has the lives of women. too often, herstory — what a difference one vowel makes — is forgotten entirely if it was ever known at all. occasionally, a woman manages to become a footnote — a brief mention that she lived and died and, somewhere in between, did something remarkable enough for us to bring our eyes to a ridiculously small font at the bottom of the page.

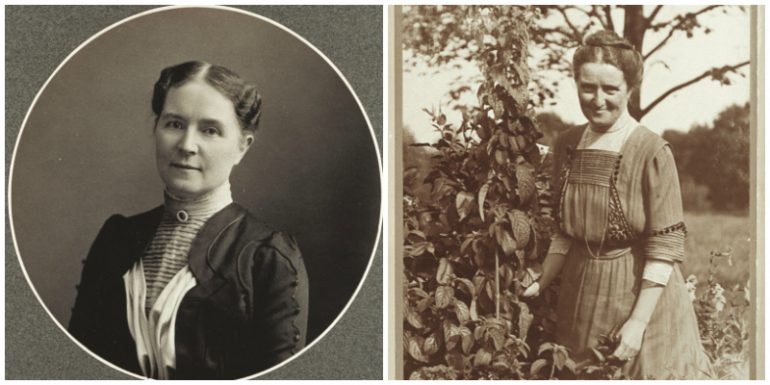

But some women refused to be footnotes. They refused to follow the so-called rules, choosing instead to follow their hearts and minds. Mary Delafield Sturges and her daughter, Ethel Sturges Dummer, are two such women. Strong, outspoken and driven, they loom larger today than the men of their rich and powerful clan — proving once again that sometimes the fairer sex is better able to make life fairer for all of us.

Even though I have written about dozens of historic estates on the shores of Geneva Lake, I can’t keep the millionaires straight. Was it the bicycle maker or the appliance manufacturer who commissioned that palatial home on the hill? Where does the chewing gum empire start and stop? The man who built the company that built the cookie with a middle to fiddle with, what side of the lake was he on? Without references or turn-of-the-century plat maps, all that wealth blurs together. While I have chewed Wrigley’s Gum, ridden a Schwinn Bicycle, washed in a Maytag, and eaten hundreds of Oreos whole — I prefer not to consume them in three acts — I feel no connection to their place on our shoreline.

But I do feel a connection to the shoreline behind the Lake Geneva Public Library, and the park adjacent to it. I drive by it every day on my way to work at Lake Geneva Middle School, and every single morning, it inspires me. Some mornings, a blanket of fog hovers just above the water like a stranded passenger waiting for the last flight home. Other mornings, the sun is visible and an early morning light filters its way through a canopy of maples and white oaks as if a window shade were being slowly raised.

There is peace on this slice of lakefront, and it’s delivered daily by Mary Delafield Sturges — a wealthy woman who knew most people would never own a piece of this shore but still had a right to.

To really drop anchor with Mary, you need to talk to Chris Brooks. A retired seventh grade teacher and Lake Geneva native, she was asked several years ago by the owners of Covenant Harbor, a year-round, lakefront church camp, to don period attire and tell Lake Geneva’s story through the voice of a woman once here.

“You can’t always find a lot on the women,” says Brooks. “I read what I could on the different families, and I came back around to a really strong feeling, a really strong connection to Mary Sturges.”

What drew Brooks to her alter ego?

“I think it was her family,” says Brooks. “The way she raised her kids, her whole connection to the library and the various philanthropy she supported. With her, I was feeling like I was teaching in the year 2000 the same way she was teaching her daughters to work and be productive in society. I was doing the same thing she espoused so long ago.”

What Mary espoused, in a nutshell, was better life for some of society’s most vulnerable citizens — even if it pushed the strict societal standards of the day. The daughter of John and Edith Wallace Delafield, she was born in Memphis, Tenn., on July 30, 1842. Her father was a lawyer and her life privileged.

In 1862, she would marry George Sturges in Duncan Falls, Ohio. The son of Solomon and Lucy (Hale) Sturges, George was one of nine children. Solomon made his mark and tremendous fortune in grain storage, ultimately settling in Chicago. Lucy’s mark — using a measure devoid of dollar signs — was even bigger: She helped runaway slaves find freedom. George would eventually make his own millions in banking.

Solomon and Lucy’s marriage was said to be as much a love story as it was a true partnership. The same is said of George and Mary Sturges. The couple would have nine children, with six surviving into adulthood, and they expected as much intellectually from their five daughters as they did their only son, George Jr.

When George, the founder of Illinois Trust and Savings, died in 1890 at his Lake Geneva residence Snug Harbor, he was only 52 and his assets considerable. In his will, he assigned their management not to his brothers or his only son, but to his wife.

“I’m sure a lot of (Mary’s) strength came from the kind of man George was,” says Brooks. “She really was his partner, which a lot of women weren’t in that time. When he died, he left it all to Mary. He didn’t leave it to an executor or a man to manage. He left it to her.”

At the time of George’s death, the Sturges family had strong ties to Lake Geneva. Like many, they arrived here in the 1870s. George’s siblings — Shelton and Buckingham — also had estates here. Shelton’s Maple Lawn, Buckingham’s Fairfields, and George’s Snug Harbor would inspire future generations to build here as well (see page 40).

Finding Mary

To Brooks it’s ironic that a woman so tied to these shores would leave behind so few clues of her life.

“I think that there’s a lot of missing pieces, for me, in her particular history,” says Brooks, “and you have to rely on the history of the men, and the next generation, to create the portrayal.”

The great eraser that is time, however, doesn’t always get everything. In Mary’s case, what hasn’t been erased by history reveals a woman with strong ideas about the role of women in civic life. Her stipulations in donating the cottage and land that would become Lake Geneva’s first dedicated library made that clear.

In 1894, Mary donated a cottage (inhabited by the family in 1871 before Snug Harbor was built) and two adjoining lots to the City of Lake Geneva to be used as a public library. A library committee was formed, local collections were merged — making a grand sum of 1,500 books — and the library opened its doors to the public in August 1895.

“When she donated the library to the city, one of the requests was that the board of directors have a majority of women,” says Brooks. “In many ways, it was unheard of. But she was a part of a group of women who did so much. They got things done.” Among the things Mary helped get done around here was the establishment of the Episcopal Church, the Lake Geneva Country Club and the YMCA. In Chicago, the Field Museum would name a hall after her for her support of North American archeology expeditions. While Brooks doesn’t think Mary wouldn’t have called herself a feminist, she says her life was lived with a “sense of a feminist cause,” an influence surely felt most deeply by her daughter and third child, Ethel Sturges Dummer.

In her book, Ethel Sturges Dummer: A Pioneer of Social Activism, Ethel M. Lichtman, the granddaughter of Ethel and great-granddaughter of Mary, writes:

“By far the most important influence on developing young Ethel’s interest in community service was the example set by her mother. At the end of the century, Mary Delafield Sturges was becoming interested in supporting a group called the Juvenile Protective Association (JPA), in which her daughter would soon become heavily involved. In 1889, some members of the Chicago Women’s club had been concerned that the same court that handled criminals dispensed decisions relating to hapless children. Interested in improving conditions for children in police stations and jails, they formed the JPA and drafted a bill proposing a Juvenile Court. After nine years of hard work, the Illinois State Legislature passed a Juvenile Court Law. The Chicago Juvenile Court, the first in the world and an example for many others, opened in 1899.”

But passing a law means nothing if there are no funds to implement it and that was exactly the case with this legislation. Even though she would never have the right to vote in an election, Mary wasn’t willing to let children suffer at the hands of politicians. The funds for the court to hire its first probation officer would come from her. So quiet was her donation, though, that Ethel wouldn’t learn of it until years after her mother’s death.

Ethel, I’ve Got an Idea

Born in 1866, Ethel would marry Francis Dummer, the vice president of Northwestern National Bank, in 1888 at Snug Harbor. The couple would have five children, four girls and a boy. Their son would die before his first birthday. The Dummers would commit their lives to Progressive reform, but their daughters were not ignored. Believing traditional schools thwarted the development of the whole child, they hired private teachers. In addition to wanting their girls to be great thinkers, they also wanted them to sculpt, paint, dance, and act. The Glory Hole, a large closet in their Chicago home, was filled with costumes and objects to inspire the imagination. In addition to their vow to love one another, they also promised to raise children in the absence of fear — hence Ethel’s frequent need to return inside when Francis would have the girls swing on a professional trapeze bar outside their Chicago home.

At their Lake Geneva residence, The Orchard (also known as Dummer’s Hill), the girls spent most of their days outside, running, playing and sometimes scaling the roof with their father. Built in 1898, and still standing, it also featured a playhouse built, in part, by the girls.

In examining the influence of Ethel Sturges Dummer and other women activists in Reproductive Health, Reproductive Rights: Reformers and Politics of Maternal Welfare 1917 – 1940 (Ohio University Press, 2003), scholar Robyn L. Rosen reveals a woman who wore a feminist label as comfortably as a favorite sweater. Rosen writes:

“Along the spectrum of concern for the welfare of mothers and children, Ethel Sturges Dummer was unique in her unapologetic advocacy of women’s emancipation, her critique of conventional morality, and her dedication to vulnerable citizens.”

One singular issue introduced Ethel to the world outside her protected life: Child labor. In 1914, she wrote in her memoirs that the elite circles in which she moved gave her “no conception of what life was like for the other 98 percent of humanity.” Her spiritual rebirth, she continued, came in 1905 while reading of the horrors experienced by children in factories and she’d be moved to pick up where her mother left off, joining the JPA and child labor reform groups.

That a woman whose wealth was so intricately tied to the status quo would be moved to act as she did speaks volumes. Over her life, she embraced a number of other causes desperately in need of a patron saint. The plight of unwed mothers, the psychological needs of prostitutes, education reform, and maternal and child welfare would become her vocation.

In 1908, she founded the Chicago School of Civics and Philanthropy, later known as the University of Chicago School of Social Service Administration. In 1909, she provided the funds to start the Juvenile Psychopathic Institute, where neurologist William Healy’s ground-breaking studies would disprove the long-held theory that bad boys and girls are hard-wired for crime. Healy’s work would shift the treatment of “incorrigibles” from punishment to rehabilitation.

Though she never held a job in the traditional sense, her husband called her a “switchboard.” Like the telephone operators of her time, she plugged progressive thinkers into funding and resources and helped broadcast their work to audiences around the world. Before Lucille Ball made “Ethel, I’ve got an idea” a part of the pop culture lexicon, Ethel had probably heard it several hundred times. But to think of her only as a wealthy woman with Social Register contacts diminishes her role.

More than a philanthropist, she’s recognized by leading sociologists as one of the most influential women of the 20th century. Some of the nation’s most promising social reforms happened, in part, because of her intellectual and financial backing. Not surprisingly, her views were highly radical for any woman of her time — but particularly for a woman of her economic background. In an early 1900s essay on feminism, she didn’t mince words:

“If the unwed mothers were given comfort and courage instead of condemnation, the ranks of prostitutes would be depleted.”

A trustee of Hull House, she worked closely with its founder Jane Addams and other leading women activists. In a 1915 letter, Addams praised her friend for her work in establishing the psychopathic clinic at the Juvenile Court, calling it “. . . one of the most substantial pieces of work in that field.”

She never learned to drive, but that didn’t keep her from covering a lot of ground. Even tuberculosis was unable to stop her. Recovering in her southern California home, she championed the development of maternity hospitals and began formulating ideas to keep delinquent teen girls from joining the world’s oldest profession. Compassion, not judgment, guided her every step. To a friend she wrote:

“The stupidity of our past intolerance quite overwhelms me. When one visits the venereal disease hospitals and finds these ‘wild women’ to be pitiful children, sadly in need of help.”

ALWAYS A MOTHER

In the archives of the Arthur and Elizabeth Schlesinger Library on the History of Women in America at the Radcliffe Institute, are 57 boxes acting as a sum total for the life of Ethel Sturges Dummer. Donated by her daughters, they are letters, photographs, tributes, speeches, essays, professional papers, newspaper clips, and photographs. Ethel received an honorary Doctorate from Northwestern University in 1940 and went on to sponsor child development courses there. Her writings include Why I Think So — The Autobiography of an Hypothesis (1937), The Evolution of a Biological Faith (1943) and What is Thought? (1945).

Though she never said so in her writings or speeches, her unwavering motivation for child and maternal welfare had to be hugely personal. Her only son died in infancy. For all her efforts in furthering the wellbeing of women and their unborn and infant children, she couldn’t save him.

When she returned to Lake Geneva each summer, as she did until seven years before her death in 1954, she must have thought about him. I am told that’s a hole that can never be filled. But did she find some measure of peace in the lives she did help save?

Did she think about the woman who appealed to Julia Lathrop, the chief of the U.S. Children’s Bureau on Oct. 19, 1916? Isolated in a remote corner of Wyoming, the woman wrote Lathrop asking for publications on how she could more safely deliver her third child. In detail, she shared circumstances of her two previous deliveries, circumstances that killed most women.

“I am 37-years-old and so worried and filled with perfect horror at the prospects ahead. So many of my neighbors die at giving birth. I have a baby 11-months-old in my keeping now, whose mother died. When I reached their cabin last November, it was 22 below zero, and I had to ride 7 miles horseback. She was nearly dead when I got there and died after giving birth . . . I am far from a doctor and we have no means, only what we get on this rented ranch. I also want all the information on baby care, especially right young, newborn ones. If there is anything I can do to escape being torn again won’t you let me know. I am four months along now, but have quickened yet.”

I am very respectfully,

Mrs. A – C – P – Hutton Ranch Burntfork, Wyo.

This letter, written by a woman who must have viewed childbirth as an eight-pound executioner, is here in these dusty archives because Julia Lathrop shared it with Ethel. Longtime partners in maternal welfare research, Lathrop turned to her wealthy friend because sometimes when two women want to get something done, they don’t wait for the government to step in — especially if said government hasn’t even bothered to give them the right to cast a ballot yet. So in the quiet way she was said to have, a way much like her mother’s, Ethel made certain a Wyoming mother she’d never laid eyes on had the professional obstetrical care she needed during “her delivery and confinement.” The check she wrote after reading this letter didn’t help this one lone mother. It helped hundreds of women just like her, providing the funds necessary for visiting rural nurses.

Like most of my favorite feminists, Ethel was a mother at her core. A mother who didn’t check the political winds before righting a wrong, a mother who knew prevention really is the best medicine, a mother who drew from her own mother’s example on how to leave a place better than you found it.

When I walk through Library Park in the early morning, I can’t see Mary and Ethel. Still, I know they’re here. And with every wave that comes to shore, I tell them, Thank you.