By Anne Morrissy

Passengers on Lake Geneva Cruise Line’s popular boat tours get a waters-edge view of some of the most opulent homes in Wisconsin, and nearly everyone comes away with a favorite. For those who appreciate historic estates with a genteel classical influence, the Lake Geneva homes designed by the Chicago architect Howard Van Doren Shaw may prove to be the ones that truly steal their hearts.

Shaw’s designs date to the first quarter of the 20th century, and yet they have unquestionably stood the test of time. The homes he designed on Geneva Lake for wealthy Chicagoans have remained remarkably resistant to the wrecking ball, despite changing tastes and the logistical challenges of transitioning an older home into the modern era. In 2015, Chicago architect Stuart Cohen of Stuart Cohen and Julie Hacker Architects wrote Inventing the New American Home, a book about Shaw’s work, and he attributes this timelessness to Shaw’s design sensibility. “The period around 1900 was a period of enormous social change [in America] with the rapid growth of the American middle class,” Cohen explains. “And so the kinds of houses that even very wealthy people wanted reflected a greater informality and a more relaxed lifestyle, particularly in their country homes.”

SOCIALITE ARCHITECT OF PRAIRIE AVENUE

Howard Van Doren Shaw was born in 1869 in Chicago, making him one of the few Chicago architects of his era to claim native status. Shaw was born into the upper elite of Chicago society: his father Theodore was a successful dry goods merchant who served on the planning committee of the 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition, and his mother was a Van Doren (of the prominent old New York family) and a trained painter who attended the School of the Art Institute of Chicago and exhibited her work throughout the country during her lifetime. Shaw grew up on Calumet Avenue in the fashionable Prairie Avenue District, and attended the Harvard School for Boys in Hyde Park before heading to the East Coast to attend college at Yale University.

Following his graduation from Yale in 1890, Shaw enrolled at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, one of the few schools in the country at the time to offer a degree in architecture. The program at MIT emphasized the aesthetic of the Ecoles Des Beaux-Arts, an influential Parisian school which favors classical arts and architecture from Ancient Greek and Roman influences. Shaw’s designs demonstrated this training throughout his career. However, Cohen feels Shaw was able to transcend his classical influences to create something new in home design. “Shaw was happy to work with traditional forms,” he explains. “But one of the arguments that I make in my book is that while Shaw never tried to invent a new vocabulary of architecture, he was part of a group of architects who were in fact transforming the American house.”

After receiving his architecture degree, Shaw traveled extensively in Europe, where he was greatly influenced by the new Arts and Crafts movement emerging from England, particularly the work of architect Edwin Lutyens. Although Shaw’s own summer home in Lake Forest demonstrated his clear preference for the English Arts and Crafts style, his exceptional training allowed him to excel in a variety of architectural styles, as dictated by the preference of the client. Shaw apprenticed with venerable Chicago architecture firm Jenney and Mundie before establishing his own firm in 1894.

During his more than three decades of work, Shaw proved to be an extremely prolific architect, working on residential, commercial and civic projects. Before he passed away in 1926, the American Institute of Architects awarded Shaw a Gold Medal, its highest award, recognizing him for his exemplary achievements in architectural design. Unfortunately, following Shaw’s death, many of his office files were lost and no complete record of his work exists to this day. Historians like Cohen have worked to assemble records from homeowners, collaborators and museum collections to create as comprehensive a list of Shaw’s work as possible. Based on this research, we know that Shaw designed at least six homes on Geneva Lake, five of which still stand today. (Hubbard Carpenter’s Rehoboth has been demolished.)

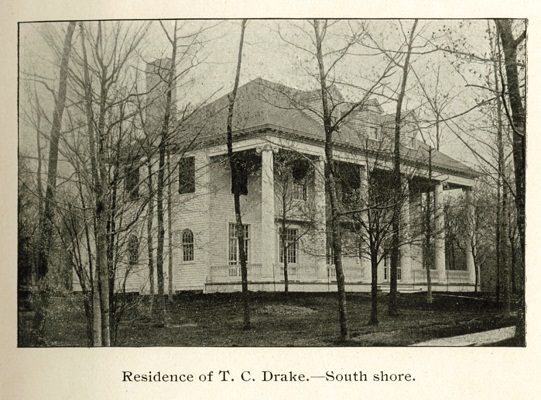

SHAW’S FIRST LAKE GENEVA COMMISSION: ALOHA LODGE

At the turn of the 20th century, Tracy C. Drake of the prominent Chicago hotelier family hired Shaw to design a country home on Geneva Lake’s South Shore for him to enjoy with his wife, Annie Daughaday Drake, and their two young sons. Drake requested a Southern Colonial-inspired home from Shaw, which he named Aloha Lodge after the family returned from a formative trip to Hawaii where they befriended the deposed Queen Liliuokalani. A large veranda facing the lake was supported by imposing, 25-foot-tall Ionic columns, demonstrating Shaw’s BeauxArts training, though the overall effect of the home is described in a 1939 Chicago Tribune article as “pure American in type.”

Inside, Shaw’s signature open-plan design surprised the article’s author, who remarked, “In the lodge, no space has been wasted on halls or walls. One enters the wide door… and comes directly into the large living room, 24 feet wide by 44 feet long. Across the room from the carriage driveway door is another door, a long glass door that opens upon the wide veranda.” The article goes on to praise everything from the Colonial-style fireplace to the mahogany balustrade on the staircase. The semicircular dining room (“a charming room”) featured white paneled walls and French windows that also opened on to the veranda.

Shaw was famous for demanding top quality workmanship in all of the homes he designed. Although he was not a trained craftsman himself, he acquired enough on-the-job knowledge of masonry, roofing, carpentry and painting that he would occasionally pick up tools and do the work himself during the construction of his homes. “There are stories about Shaw telling workmen on his jobs to rip out work that he found unacceptable,” explains Cohen. “Even to extent of taking tools away from workmen and saying, ‘That’s not how you do it, let me show you.’ Shaw built very solid homes.”

HOUSE IN THE WOODS

In 1905 (around the same time he was designing Hubbard Carpenter’s Rehoboth on the north side of Geneva Bay), Shaw designed another elegant summer home for Geneva Lake. Chicago businessman and Director of the University of Chicago Adolphus Clay Bartlett commissioned an architecturally unique home he named House in the Woods. Bartlett’s son Frederic Clay Bartlett, an accomplished painter and muralist, collaborated closely with Shaw to design what Clay later explained was a whimsical take on country living.

(“Most people take their country house entirely too seriously,” he told a reporter for Country Life in America.)

House in the Woods included a painting studio for Frederic Clay Bartlett, separated from the main residence by a loggia, a terrace and a courtyard containing a fountain and an original Clay mural. According to Cohen, the detailing of both buildings — particularly the trellising of the walls — was reminiscent of the Viennese Secessionist movement and combined elements of the Arts and Crafts and Art Nouveau movements. At House in the Woods, Shaw made liberal use of the triple archways that would appear on subsequent homes he designed on Geneva Lake. The front of the house was defined by arched bay windows in the living and dining room.

Cohen particularly admires the way the home’s original design created a sense of drama for the arriving guest. “You used to drive through the woods and come to a turnaround in front of the house… and you walked through a big entryway, and the entrance to the house was in that covered space,” he explains. “On the other side you had a wall with three sets of French doors that opened to a hallway… which then opened to a screened porch/ loggia. So instead of walking in and seeing straight to the lake, you’d have an entry sequence that carefully… channeled the views out to the lake.”

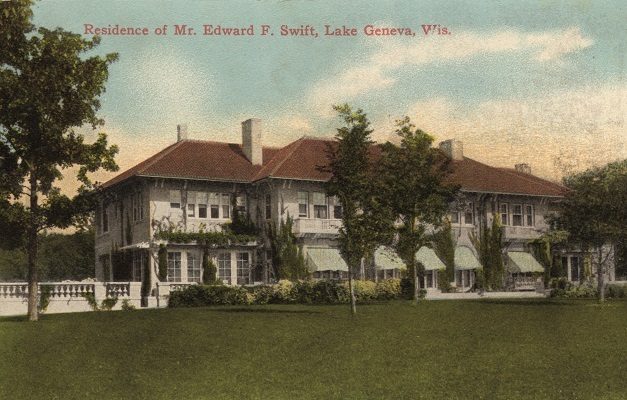

VILLA HORTENSIA

The following year, Edward Foster Swift, son of meatpacking scion Gustavus Swift, commissioned Shaw to design his country home on the north shore of Geneva Lake. Villa Hortensia, named in honor of Swift’s wife Hortense, bore a slight resemblance to House in the Woods, though in his book, Cohen describes Villa Hortensia as “vaguely Mediterranean [in] style” with Arts and Crafts details “on a grander scale.”

The driveway entrance featured a covered entry porch with three arched doors supported by classical Doric columns. Shaw repeated this arrangement on the lake façade in the three arched French doors leading to the front patio and the lawn and lake beyond, a connection between the house and the landscape that was a hallmark of Shaw’s designs. Shaw collaborated with famed landscape architect Jens Jensen on several projects, including Villa Hortensia, ensuring that the home’s interior spaces would flow easily into the landscape. The front patio ran the entire length of the house and provided the liminal space between the inside and the outside. According to Cohen, the design of Villa Hortensia “is an idea about connecting the house to the landscape that’s often linked to the Prairie School, but Shaw was doing it with a different set of architectural forms. The connection of inside to outside was something that Shaw felt very strongly about.”

Inside, Shaw’s design for Villa Hortensia included a large vaulted gallery, a guest suite, a spacious sunken living room, a reception hall with a fountain and ceramic pool, and a circular staircase to the second floor gallery and bedrooms, among many other elegant aspects.

ALTA VISTA

It would be more than a decade before Shaw designed another home on Geneva Lake. In 1919, Colonel William Nelson Pelouze and his wife purchased Alta Vista on Geneva Lake’s north shore, but they only spent one summer in the grand Victorian-style home before it burned to the ground that fall. Pelouze and his wife Helen wasted no time in hiring Shaw to design its replacement. Of all of Shaw’s homes on Geneva Lake, Alta Vista perhaps best demonstrates Shaw’s European training. A Chicago Tribune article from 1939 described the home as “similar to those surrounding many Italian lakes.”

Like House in the Woods, Shaw put careful thought into the approach to the house from the road. A circular Italian-style garden containing carefully manicured hedges and evergreens, marble benches and balustrades, and a fountain and fish pool welcomed guests to the entry. On the inside of the home, Shaw designed a vaulted loggia running the entire length of the home on the lake side. Small, Italian-style balconies adorned the windows of the second-floor bedrooms.

The current homeowners bought Alta Vista more than 15 years ago and say that Shaw’s design is what initially drew them to the house. “We loved that every bedroom has a view of the lake, and that [the home] was open-floor-plan before open-floor-plan was even a thing,” explains the wife. “We love that we can be in the kitchen and see kids playing in the family room and everybody still feels like they’re part of the same house and party.”

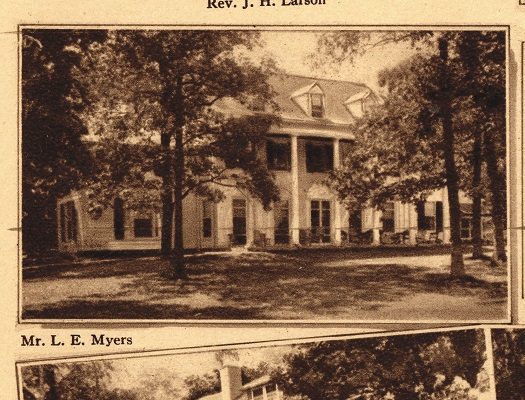

ALLEGHENY

Just a few years before his death at the age of 57, Shaw completed what would turn out to be his final commission on Geneva Lake. In the late 1910s, Lewis E. Myers purchased a portion of the massive former Loramoor estate and in 1924 he built Allegheny, named for his birthplace near Pittsburgh. Allegheny was a Shaw-designed Colonial home remarkably similar in appearance to Shaw’s first Geneva Lake commission, Aloha Lodge. Myers owned a Chicago construction firm and served as president of the Southern Electric Company, which provided electricity to the Lake Geneva area from 1916 to 1929 before being purchased by Wisconsin Power and Light. He was also an avid orchidist, and raised hundreds of varieties of the exotic flowers in his greenhouses on the property.

Like all of Shaw’s homes on Geneva Lake, Allegheny’s design featured a massive open living room at the center of the house. A 1943 Chicago Tribune article estimated it to be 60 feet by 35 feet, and described the room’s French doors leading to the pillared portico on the front of the house, “giving a vista of the lawn and lake that at first sight seems to be part of the room.” The refined, traditional living room — complete with painted mural wallpaper — contrasted with the informality of the wood-paneled card room next to it. The formal dining room featured arched built-in bookcases flanking another set of French doors.

Cohen points out that the style of both Aloha Lodge and Allegheny were unusual for Shaw. “The Colonial houses with the colonnaded porches, those houses are totally atypical of Shaw’s work,” he explains. In fact, when looking at the body of Shaw’s work, most of the homes he designed on Geneva Lake demonstrate a divergence from Shaw’s personal preferences and suggest significant input from their owners. But as Cohen points out, “Shaw was very a popular architect and I assume he got that way by pleasing clients.”

SHAW’S HOMES TODAY

Although most have been altered slightly, all five of Shaw’s homes that remain on Geneva Lake today are still under private ownership, enjoyed by a new generation of families who choose to spend their summers here. The timeless grace of these homes ensures that they are still admired by the area’s tourists, and their continued presence connects the history of the early 20th century to the modern Lake Geneva of today. This is due in no small part to the sensibility of their architect, Howard Van Doren Shaw. “There was a sense of scale to [Shaw’s houses],” Cohen says. “Even the grand houses had a sense of comfort and intimacy that you don’t get in any of the really big, palatial places of the era. Shaw’s houses just felt comfortable.”