By John Halverson

Jim Gee’s business card never had a title. It’s not only out of modesty — though that plays a part — but it’s also because he’s a man who naturally wears many hats. “I was once told ‘you really think outside the box.’ My reply: ‘I didn’t know there was a box.’”

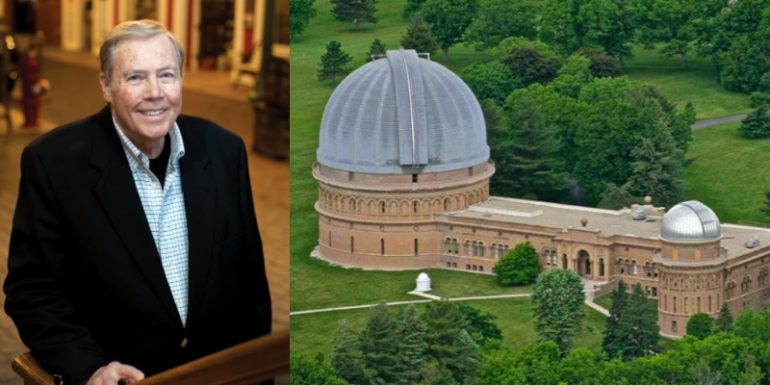

Gee, a towering man full of geniality, has been a guiding light in the Geneva Lakes area for a long time. He was director of operations at Yerkes Observatory in Williams Bay for 27 years — right up to the day it closed in October 2018. He was the face of the observatory, frequently acting as tour guide for a place he loved.

Gee’s days at Yerkes ended unexpectedly. A friend broke the news to him as he was driving home from Chicago. The University of Chicago, which owned Yerkes, had decided to close the iconic observatory. The friend had read about it in the Chicago Tribune and called Gee to see what was up. It was all news to Gee; he didn’t have a clue even though he had just met with university officials on campus only hours before.

He was stunned. “Yerkes was so loved internationally,” he says, recalling his thoughts that day. “It was the birthplace of American astronomy and they were throwing it all away.”

Founded in 1897, it was often called the “birthplace of modern astrophysics.” Albert Einstein even visited there. The observatory, which was dedicated in 1897, is known for its giant 40-inch refracting telescope, housed in a dome overlooking Geneva Lake. It was the largest refractor ever successfully used for astronomy. The building itself defined an era. Anyone who has been there can attest to its history.

As for the speculation that the university closed Yerkes because it was old school, Gee says “sure it is!” It’s age, he believes, is a badge of honor. “That’s the way it’s supposed to be.”

The closing really hit home for Gee when, on the final day, his key to the building didn’t fit the lock.

GEE’S UPBRINGING

Ironically, Gee’s association with Yerkes and the University of Chicago goes back 78 years when he was born at a hospital on the university’s Hyde Park campus.

He grew up in hardscrabble Chicago. His great-grandfather, a cabinetmaker by trade, started a lumber and millworks business in the 1870s. Gee started working for the family companies at age 12. Along the way he dabbled in carpentry, was a teamster, a layout designer for newspapers and even sold, of all things, garages door-to-door.

His father and uncle created the first U.S. home improvement center in Chicago in 1947, which became the prototype for stores like Home Depot.

As a teen, his friends spanned the socioeconomic spectrum — “members of the football team, gear heads and egg heads,” he says. That diverse experience paid off later in his ability to be comfortable with groups as diverse as teamsters and bankers and fit into a room full of both CEOs and scientists.

Gee credits his upbringing for giving him a wide range of expertise. And those variety of interests are exemplified by his two bachelor’s degrees — one in fine arts and the other in geology, plus an MBA from the University of Chicago. You could say his background is the meeting of yin and yang, art and science.

“Running a family-owned business requires expertise in multiple areas, some of which apply to working for a university,” Gee says. “Accounting, finance, employment law and marketing are basic skills, which are common threads that apply to all. An MBA degree is, of course, the formal credential; common sense and street moxie supply the rest.”

That amorphous view of himself was perfect for Yerkes. “I’ve always enjoyed accepting a job, task or challenge that had nothing to do with my job description,” Gee states.

At Yerkes he was known as the go-to person. “Faculty came to me to get stuff done for them. So, my self-given title of ‘guy who gets stuff done’ makes sense. If it made common sense to violate established university protocol, I would do it.”

Gee was known as “a player’s coach,” to steal from sports jargon. “I genuinely cared about the people who worked for me. I paid attention to their input and always gave them credit when I used their ideas,” he explains. “Everyone has strengths and weaknesses. I played to each employee’s strengths.”

He encouraged his employees to act like managers instead of clerks. “Clerks are comfortable saying, ‘no,’” he says. Managers figure out ways to say, ‘yes.’”

Gee’s management style followed a philosophy which kept the best interests of Yerkes in the forefront. For instance, he would occasionally bring in engineers to the university without appropriate credentials. “One of the best research engineers at Yerkes had a degree in forestry,” Gee says.

PERSISTENCE PAYS OFF

When he applied for the job at Yerkes, he knew nothing about it. He was looking for work after the closing of his family businesses. He saw an ad for the job in The Wall Street Journal. They were seeking a business manager for the Center for Astrophysics in Antarctica — a job for which he had few qualifications, on paper at least. That didn’t dissuade him from making a cold call to the University of Chicago.

“I was in the process of interviewing for various CEO positions in the Chicago area. We had a summer home in Lake Geneva so I thought it might be interesting to see what the position was all about,” he says.

“I answered the university’s ad by simply showing up at the front door. The faculty and staff were not really prepared to interview but I convinced them to set a time later that afternoon for a chat.

“They were looking for someone with a doctorate in astrophysics or engineering for the position,” Gee says. “I suggested that they really didn’t need another Ph.D. for this position, rather why not consider someone with a business background who had real world experience running a company. I was a good salesman,” he says.

Besides his work at the observatory, Gee established the university’s engineering center which employed, at its peak, 30 engineers, technicians, machinists and staff, at five university locations in places as far flung as the South Pole.

His office at Yerkes was previously occupied by Subrahmanyan Chandrasekhar who won the Nobel Prize for his black hole discoveries.

“I was in Chandrasekhar’s space,” says Gee. When asked if he felt Chandrasekhar’s presence, Gee says, “Better than feeling his presence, I knew him.”

As he had done while applying for the Yerkes job, Gee made a cold call to Chandrasekhar’s office on the University of Chicago campus. He explained to Chandrasekhar’s secretary that he had nothing to talk about except that the two occupied the same office.

“I was let in because there was someone at his desk who didn’t want to talk about black holes or mathematics.”

Instead, Chandrasekhar was delighted to talk to Gee about the early days of Yerkes. “We had some very interesting conversations, none of which were about science or astronomy.”

A PRESENCE IN THE COMMUNITY

Gee settled into the Geneva Lakes area, where he and his wife live in a house built by his son. In his garage is a 1930 Model A Ford that he works on. In the past he counted aviation as a hobby and kept a plane at Chicago’s Midway Airport. He also enjoyed motorcycling with staff members at Yerkes.

In addition, Gee has been a member of local boards of directors. He serves on the Geneva Lake Association board, the Environmental Education Foundation board and the Geneva Lake Museum board — where he was once president.

Why is he involved in so many groups? “Because I feel I can make a difference,” he says.

YERKES’ FUTURE

In November 2019, an agreement in principle was announced that the University of Chicago would transfer Yerkes Observatory to Yerkes Future Foundation. It read:

“YFF’s objectives include resto- ration and refurbishing of the telescopes and building, reopening the space for visitors and establishing educational, research, seminars and various additional opportunities for students, astronomers, astrophysicists and others.”

Students and faculty in the University of Chicago’s Department of Astronomy and Astrophysics have continued to do educational and research work at Yerkes Observatory.

Dianna Colman, who was profiled in the fall 2019 issue of At The Lake for her fundraising efforts, has been instrumental in forging a new future for Yerkes.

“We had to go through so many hoops, many relating to the complexities of caring for a 65,000-square-foot, 120-year-old building and that has involved permits, zoning, safety and all the legalities related to the agreement,” she says. “I can speak zoning now,” she jokes.

“We could just save the tower and have people look through telescopes,” she says. “But we want to make it much more expansive.”

Colman and Gee have known each other for years. As president of the Geneva Lake Association, Gee proposed funding a Geneva Lake fire boat for the Town of Linn; Colman was the chair of the committee that did the fundraising.

“He’s so helpful and so sweet,” she says. “If I could clone him I would.”