By Jill Westberg and Carolyn Hope Smeltzer | Photography: © Deborah Dumelle Kristmann

Geneva Lake may be best known for the many elegant mansions that have been built on its shores over the decades, but nestled in between those opulent displays of wealth there have always been organizations of a more egalitarian nature—religious and social justice camps, open and available to people of a wide variety of classes and backgrounds. The idea of these camps’ founders was to make the beauty of the area available to anyone who wanted to experience it, and to hopefully improve people’s health and mood in the process. Some of these camps survive today, but many others have been lost to development and changing social rules. The history of the camps often highlights the challenges and creative solutions of the era during which each camp flourished.

Many of the camps provided a getaway for working-class women and children who were otherwise living difficult lives, often toiling in unregulated, unsafe conditions in the city. Other camps provided a wholesome environment for young women to improve their moral and spiritual education. Others aimed to improve access to nature for people of color, who had traditionally been welcome in the Lake Geneva area only as domestic help. Each camp offered an escape from the heat, dirt and discomfort of the city to those who were lucky enough to visit.

Below we’ll introduce you to three camps that have touched the lives of many for over 100 years. Although just a snapshot of the camps that surrounded Geneva Lake, their stories represent common threads: the crystal clear waters of Geneva Lake, the lush green landscape that welcomes each visitor, and the introduction to new friends, thoughts and ideas.

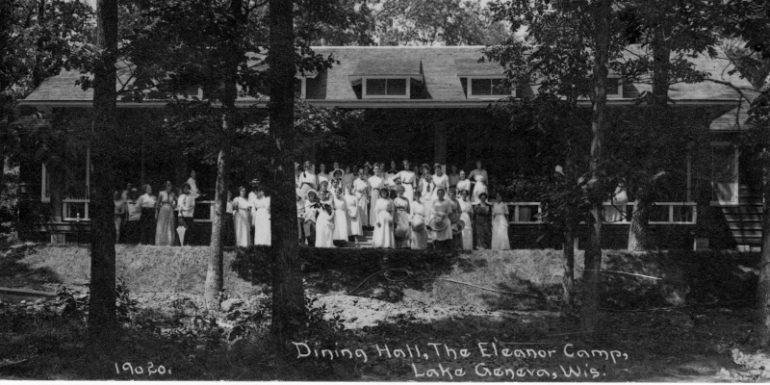

ELEANOR CAMP (1909-1953, NOW WESLEY WOODS RETREAT CENTER)

In 1898, Ina Law Robertson joined an elite group of women at the newly coeducational University of Chicago’s Divinity School. While there, she met many young, unmarried women who worked as sales clerks downtown and struggled to thrive on $3 to $7 a week. Robertson decided to develop housing for these and other working women through the creation of the Eleanor Women’s Foundation, which opened the first Hotel Eleanor in Hyde Park. Robertson named the foundation and hotel (really more like a women’s dormitory) for her friend and benefactor, Eleanor Law, embracing a play on words: Eleanor is the Greek term for “light.” (Robertson felt the light represented the gifts the women brought to Chicago.)

The original Hotel Eleanor contained 28 rooms and filled up immediately, so Robertson moved it to a building that could house 81 women, adopting the name Eleanor Club. Eventually the Eleanor Club expanded to six residences throughout Chicago. (The last Eleanor Club Residence was built in 1956 on Dearborn Parkway.) At their height, the residences provided affordable, safe housing to more than 600 working women at a time.

The Eleanor Club Residences demanded high moral standards of the women who lived there. Each woman submitted letters of recommendation along with her credit check and key deposit. When approved, she received a “Values and Guidelines” manual. But adhering to the rules seemed a small price to the thousands of women over the decades that were able to live inexpensively in a safe environment for up to two years, with breakfast and dinner provided. They often enjoyed the added benefits of strong friendship with their fellow residents.

Although the Eleanor Club Residences featured simple rooms and shared bathrooms, the common rooms could be quite elegant. In the downtown Central Eleanor Club, members could dine in the club’s tea room and take classes in etiquette, gymnastics, folk dancing, drama, millinery and English. The residences flourished until the 1960s when social changes made them obsolete.

FROM CLUB TO CAMP

The early success of the Eleanor Clubs inspired Robertson to expand the concept. She believed that single, working women should be able to enjoy an affordable vacation—albeit one that was chaperoned, in keeping with the social mores of the day.

Before investing in land, the Foundation experimented to see if women would travel to Geneva Lake and enjoy their camping experience. In 1909, the Eleanor Women’s Foundation rented space at Kaye’s Park, west of Black Point. That summer, the camp hosted 45 Eleanor Club women. The next year the camp moved across the lake to Camp Collie (modern-day Conference Point Camp) where it remained for three seasons.

In 1912, the Eleanor Club acquired 10 acres of the former Stam property in Williams Bay (now Wesley Woods Retreat Center) and built a stately dining room and recreational hall. Most of the women bunked in elegant permanent tents that were furnished with books, lamps, easy chairs and writing tables.

Eleanor Camp hosted 120 single, working women each summer, in groups of between 30 and 45. Campers were not required to be residents of the Eleanor Club in Chicago, but as with club residents, they needed to submit letters of recommendations proving their “moral soundness.” Because of the low cost, single women from all walks of life and educational backgrounds enjoyed the opportunities at the camp.

Activities at Eleanor Camp were similar to many of the camps around Geneva Lake. Naturally the lake was the focal point: bathing, fishing and boating were popular with the Eleanor Campers. Florence Carlson became the lifeguard at Eleanor Camp beginning in 1927. She arranged for early morning swims, water exercises and lessons. Although Eleanor Camp did not own a sailboat, the sons of the Leonard family of nearby Rockford Camp gave rides to the women for 25 cents each. (Serendipitously, one of those women married into the Leonard family.)

“Tramping” (or hiking) proved a popular pastime, whether along the lakeshore or up through the woods to the grounds of Yerkes Observatory. The women also participated in tennis and archery on the grounds. In the evenings there were hayrack parties and bonfires where the women could roast marshmallows and sing camp songs, including their own “Eleanor Song.” True to the times, they even had an Eleanor Pledge and a camp flower: the daisy.

In a bittersweet nod to the future, the camp closed in 1953. Society no longer deemed it necessary for single, professional women to take chaperoned vacations. Opportunities were opening up to women and travel to distant, more exotic places had become easier.

OLIVET CAMP (1908-PRESENT, NOW NORMAN B. BARR CAMP)

Like Eleanor Camp, Olivet Camp had its beginnings in Chicago, in a neighborhood known as Little Hell where Presbyterian minister Norman B. Barr served at the Olivet Institute, a flourishing settlement house. In 1907, Barr was invited to speak at the George Williams YMCA Camp. While hiking the lake path, he discovered that the adjoining property, Vrailia Heights, was for sale. He envisioned the site as a delightful escape for the working-class women and children who lived near the Olivet Institute. He hoped that a week of nourishing meals, clean air and exercise might fortify them to face their taxing lives in the city.

FEE STRUCTURE ENSURES ALL COULD ATTEND

The sliding-scale payment system at Olivet Camp was unique on the lake. Three “tiers” of campers vacationed there. Wealthier families who paid in full stayed in tents, cottages or Olivet Camp’s small hotel, and their fees subsidized the camp experiences of those families who paid nothing due to financial difficulties, or working families who paid a reduced rate. To contain costs, volunteers undertook the maintenance and improvements for the camp.

Olivet Camp was overwhelmingly popular. Some nights, so many visitors arrived without a reservation that overflow guests had to sleep on porches. With high attendance and volunteer labor, Olivet Camp thrived. Because of its roots in the Presbyterian Church, Olivet Camp aimed to develop the spiritual lives of its guests. In the early years, Olivet Camp guests attended worship services at the YMCA Camp next door, but Olivet always had its own Sunday school and eventually built its own chapel as well. Guests at Olivet Camp were not required or expected to share the Presbyterian faith; many Roman Catholics and people from other Protestant faiths attended as well.

Activities at Olivet Camp included swimming, boating and fishing. Volunteers gave cooking and sewing lessons. At “stunt night,” children displayed their talents. In later years, the camp nailed a large movie screen to a tree by the lakefront and screened movies twice a week, luring nearby homeowners to join the campers.

Originally, everyone at Olivet Camp ate together in the dining hall, but eventually the cottages were equipped with stoves so guests could prepare their own meals. However, the ritual of sharing a meal continued at weekly potluck meals. Eating, playing and worshipping together created a strong sense of community, and families returned to Olivet Camp for generations.

YMCA CAMP (1890-PRESENT, NOW GEORGE WILLIAMS COLLEGE OF AURORA UNIVERSITY)

The modern-day George Williams College campus of Aurora University began its life as the Western Secretarial Institute, but was quickly renamed YMCA Camp. The camp originated in 1884 on the grounds of Camp Collie in Williams Bay. Robert Weidensall, the first paid employee of the national YMCA, advocated for the establishment of the camp in order to provide educational opportunities for the network of local executive directors of the YMCA (then called secretaries).

In addition to hosting director training, the camp served as a place where the directors could exchange ideas and methods. This proved so worthwhile that two years later, the YMCA bought its own camp property on Geneva Lake west of Camp Collie. The educational component expanded to anyone seeking leadership training in the YMCA or similar service organizations. In 1890, the YMCA established a year-round school in Chicago and named it George Williams College after the English founder of the YMCA.

CAMP ATTRACTS DIVERSITY

Even after the founding of the Chicago school, the Geneva Lake campus remained essential for summer training. The YMCA Camp (later “College Camp”) became one of the most active and diverse conference and family camps on the lake. People from around the world, of all races and ethnic groups, came to Williams Bay to attend the Y Camp. A Sioux woman attended a YWCA conference there in 1890 and noted African American scientist and inventor George Washington Carver was a student there in 1893. Welcoming diversity was a highly unusual practice for the era, but the attitude taken by the camp was summed up in this quote by one of the YMCA directors, R.C. Bell: “They came with the narrow nationalism and race-prejudice; they went away with new ideals of genuine brotherhood.”

The conferences that convened at the Y Camp ranged from conservative to very progressive. In the 1940s, the American Youth Conference included associations such as The Christian Front, the Abraham Lincoln Brigade, The Southern Negro Congress, Mexicans in the Southwest, the Jewish delegation and the United Mine Workers. The conference was so progressive that the Chicago Weekly accused it of promoting communism. However, College Camp valued free speech and open debate and continued to welcome conferences with widely varied ideologies.

College Camp also made a conscientious effort to extend its welcome to people in the Lake Geneva area, opening its worship services to everyone, attracting musicians of the highest caliber to the campus (William Garfield, Isaac Stern, Rise Stevens and Sherrill Milnes performed there), and hosting internationally renowned speakers in the fields of education, religion, health and political affairs.

When camp guests weren’t attending lectures or musical events at College Camp they participated in a vast array of activities including sailing, rowing, swimming, fishing, golf, tennis, badminton and children’s “day camps.” The camp, rooted in the YMCA, aimed to nurture the body, the mind and the spirit.

THE CAMPS TODAY

In addition to these three camps, many others have dotted the shores of Geneva Lake over the past 150 years. Local historians estimate that since Camp Collie was founded in 1874, there have been at least 18 such camps, including seven which are still operational (Covenant Harbor, Conference Point Camp and Holiday Home Camp among them). The camps have historically served and continue to serve people of all races, cultures and economic groups. The camps cater to children and older adults alike. They embrace diverse populations and make the lake available to everyone, regardless of income, ability or background.

Camp culture has helped to shape lake culture in ways that still resonate today—just ask the campers, or people who have committed their summers or even their entire careers to Geneva Lake camps. And as they have always done, the camps serve as a good reminder that nature is not reserved for the fortunate—a week at camp can be a life-changing, restorative experience for everyone who is lucky enough to spend time at the lake.