By Sarah T. Lahey

The circus is not dead. Just look at the box office earnings for the 2017 hit film, “The Greatest Showman,” which chronicles the life of P. T. Barnum, or check ticket prices for Cirque de Solei in Las Vegas (there are six different shows, performed every evening!). Even “Disney on Ice” gives a nod to the circus, since it is owned and operated by the same company that ran the Ringling Brothers and Barnum & Bailey shows. The circus remains in our hearts and minds as an awe-inspiring spectacle that has the power to transport audiences to an imaginary world – a world that was firmly entrenched, oddly enough, at Delavan Lake.

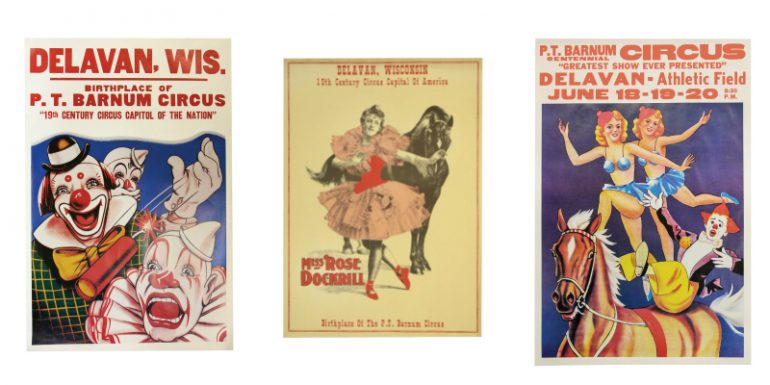

While the birthplace of the American circus technically is located in Somers, New York, this eastern locale soon lost its sway to Delavan, Wisconsin, once known as the “19th Century Circus Capital.” From 1847 to 1894, performers from more than 26 different circuses called Delavan home – that is, when they were not on the road. Delavan became the winter site for these shows, a place where they could rest their animals, store their equipment, and develop new acts.

Over time, Wisconsin became a kind of circus “incubator.” According to Peter Shrake, archivist at Circus World Museum, more than 100 circuses had their start in Wisconsin. The Ringling Brothers began their show in Baraboo, while the renowned P.T. Barnum founded his circus in Delavan. Before the state of Wisconsin even had a constitution, it laid claim to the nation’s most famous circus performers.

THE MABIE BROTHERS – VISIONARY FOUNDERS

Delavan’s circus history properly begins with the Mabie brothers. Edmund and Jeremiah Mabie grew up on a family farm in New York State, where they began developing a circus act in 1840. By 1847, they ran the largest circus in the nation, complete with 27 wagons, 125 horses and eight elephants. Their biggest elephant, Romeo, stood nearly 20 feet high and weighed 10,500 pounds. The Mabie Brothers Circus normally toured the Midwest and returned to New York in the winter, but something changed in 1847.

As local legend has it, the Mabie brothers – en route from Milwaukee to Janesville – stopped at Delavan to hunt prairie chickens and promptly fell in love with the area. Local historian Patti Marsicano notes that Delavan Lake, “lush in its primitive state,” provided the perfect spot for animals to thrive during the winter. Animal feed was important, considering that circus elephants consume up to 200 pounds of hay and 50 gallons of water per day. Marsicano adds that Delavan gave the Mabie Brothers Circus a head start over east-coast competitors who traveled to the Midwest when the season began.

After the arrival of the Mabie brothers, Delavan became a magnet for other shows. By 1858, four circus acts had followed the Mabies to Delavan. This doesn’t even take into account the “spin off” shows created locally. H. Buckley, for example, was a talented bareback rider with the Mabie brothers who soon formed his own show, called the “Grand Consolidated Circus and Menagerie.” The Holland and Dockrill families likewise came to Delavan with the Mabie brothers and then formed their own acts. This “snowball effect” led to a booming Delavan economy and a growing population.

SNAKE OIL AND SCANDAL

Not all inhabitants of Delavan, though, were pleased with the change. Delavan began as a temperance colony, founded by Samuel and Henry Phoenix, who were both devout Christians. Their Temperance Inn on Walworth Avenue, for example, allowed only “strict” Christians to stay overnight. When the temperance colony dissolved in 1845, few residents expected the arrival of a circus three years later. This abrupt shift in the town’s purpose upset long-time residents.

The real problem was reputation. By and large, circus shows attracted the wrong type of people. Marsicano explains that “snake oil salesmen,” looking to dupe the crowd or sell fake goods, often followed circus wagon trains. Long-time Delavan historian Gordon Yadon wrote that “con men and drifters” attached themselves to the circus, despite the best efforts of owners to keep them away. As the hub of 26 circuses over a span of 50 years, Delavan saw its fair share of con men. By the end of the 19th century, Delavan was dubbed not only the “circus capital of the nation,” but also “the wickedest city in Wisconsin.”

MABIE BROTHERS AS CIVIC LEADERS

The Mabie brothers, however, tried to run an honest show. They also put extensive time and money into the village of Delavan, purchasing the local gristmill and establishing permanent homes in the area. They bought 400 acres on Delavan Lake, which gradually expanded into 1,000 acres, all on the site of today’s Lake Lawn Resort.

Edmund Mabie went even further. He joined the Delavan Congregational Church, served as village president and contributed to public works. He ensured the completion of a 60-mile plank road from Racine to Janesville, which improved transportation through Delavan. Marsicano adds that both brothers “saw to the completion of the Racine-Mississippi railroad,” which ran through Delavan starting in 1856. The Mabie brothers, in short, put this Wisconsin town on the map.

P. T. BARNUM GETS HIS START

More than 20 years after the arrival of the Mabies, the biggest names in the circus business were still hanging around Delavan. One such gentleman was William C. Coup, who has been called the “greatest circus genius who ever lived.” Coup was an innovator, a visionary and a retired circus manager with time on his hands.

According to several sources, including the Wisconsin Magazine of History, Coup met P.T. Barnum in Delavan in 1870, and convinced Barnum to use his reputation as founder of the American Museum, in Brooklyn, New York, to create his own circus. Barnum was skeptical at first, but Coup – along with partner Dan Costello – convinced Barnum to try the venture.

Coup knew the tricks of the trade, but wanted to try something new. Specifically, he wanted to transport Barnum’s Circus by rail instead of wagon – a decision that would change the industry forever. In the spring of 1871, P.T. Barnum’s first circus show left Delavan by railcar. It was headed to Brooklyn, New York, where Barnum would base his new act.

Historian Gordon Yadon’s research, however, shows that Barnum merely loaned his name to the show. He was a retired museum owner by 1870, with little experience in live entertainment. As scholar A. Davies insists, “It was Coup who put the first circus on its own railroad train. It was Coup who introduced the second and third rings. Coup, not Barnum, was the real founder of the Greatest Show on Earth.”

During five years of business partnership, Barnum and Coup ran a successful show and established the “Great Roman Hippodrome” in New York, an outdoor arena that eventually became Madison Square Garden. James A. Bailey joined the venture in 1888, creating the Barnum & Bailey Circus. Meanwhile, Coup was edged out and died penniless in Florida, while Barnum reaped the rewards. William C. Coup’s dying wish was to be returned to Delavan for burial, where his gravestone can still be viewed in Spring Grove cemetery.

THE HOLLAND FAMILY LEGACY

If the departure of Barnum’s circus left a hole in Delavan’s economy, it was filled by the Holland family. The Holland family did not merely train or rest their animals in Delavan. They hosted Delavan’s longest-performing circus, with shows starting in the 1850s and continuing until 1894.

John Holland was a talented equestrian who came to town with the Mabie brothers. He and his wife, Honora, soon started their own show, known for its acrobatics. Numerous versions of the Holland family circus followed, spanning several generations. John and Honora’s grandson, George E. Holland, became a world-class equestrian who, according to Yadon, once completed “54 consecutive backward somersaults on a galloping horse.” George’s wife, Rose Dockrill, rivaled him in talent as a bareback rider.

They performed together for more than 40 years.

As late as 1935, descendants of John Holland were still practicing in the old family barn. They no longer performed in Delavan, but continued their act on the road. Marsicano states that, in total, the Holland family circus “spanned three generations and 109 years.” It is not surprising, then, that the Holland Family was inducted into the International Circus Hall of Fame in 1980.

THE GREAT VAN AMBURGH SHOW

A final show of note in Delavan was the Van Amburgh Show, owned jointly by the Holland family and James B. Sturtevant. The latter was a prominent Delavan citizen, serving on the city council and running the local grocery store.

An 1891 poster for this circus, shown above, reveals the pros and cons of circus performance. It shows, for instance, an advertisement for “African Pigmies in America” as well as a group of “Wambuti dwarves.” The disturbing nature of this image, with its overt racism and hints of Social Darwinism, showcases the underbelly of the circus world: the way in which the circus exploited people of various shapes, sizes, and colors for financial profit.

At the same time, the poster highlights a great equestrian, Miss Julia Lowande, along with a bounding jockey and elevated stages. This level of talent also epitomizes the 19th century circus: it was an artistic spectacle and a feat of human ability.

The Van Amburgh Show was one of the last to be created in Delavan. As rail travel became more popular, travel routes changed, and Delavan faded as a hub of activity. By 1894, Delavan had no active circuses in town. A generation later, most remnants of the circus were gone.

CELEBRATING DELAVAN’S PAST

There remain, however, a few reminders of Delavan’s historic role in the American circus. More than 130 persons affiliated with the circus are buried in Spring Grove and St. Andrew Parish cemeteries, both located in Delavan. Spring Grove features the graves of George Holland and his wife, Rose Dockrill, as well as circus owner George Middleton, whose body rests in a large mausoleum on the cemetery grounds.

Delavan also boasts several historical markers, including three fiberglass sculptures of a giraffe, elephant and clown in Tower Park. In 2015, the City of Delavan added to these commemorative efforts with a series of historic murals, one depicting a clown and honoring the “great circus stamp controversy” of 1966. This refers to an argument between folks in Somers, New York, and Delavan, Wisconsin, over who would issue the first-ever “American Circus commemorative stamp.” Delavan won the argument and initiated the historic, five-cent stamp featuring the star clown of the Ringling Brothers’ show.

Last but not least, Delavan has hosted iconic events over the years. In 1948, the Wisconsin Circus Centennial took place in Delavan as part of the celebrations for 100 years of statehood. Several decades later, Delavan hosted yet another centennial party for the Barnum & Bailey Circus. Countless train cars, elephants, and performers came back to town, recalling that moment in 1870 when Coup and Costello convinced Barnum to try his hand at the circus.

Whether it was the Mabie brothers, the Holland family or P.T. Barnum himself, circus “greats” did not merely spend their winter months at Delavan. Many lived and died here, serving as politicians and grocers, shop-owners and church-goers, not to mention local performers. They called Delavan their home and changed the town’s history forever.

120 YEARS OF DELAVAN’S MEMORABLE CIRCUS MILESTONES

- 1847 Mabie brothers arrive in Delavan with 27 wagons and eight elephants

- 1858 Four more circuses call Delavan home, including the Holland Family Circus

- 1864 Mabie brothers sell their circus, which moves to Chicago

- 1870 P.T. Barnum (led by William C. Coup) founds his circus at Delavan

- 1880s Circus “colony” at Delavan reaches its peak

- 1894 Holland family and other circuses closed their tents and Delavan’s circus era concludes

- 1948 Wisconsin Circus Centennial held in Delavan

- 1966 The American Circus commemorative stamp is initiated in Delavan

- 1970 Ringling Brothers and Barnum & Bailey Circus returns to Delavan to celebrate the 100th anniversary of Barnum’s circus