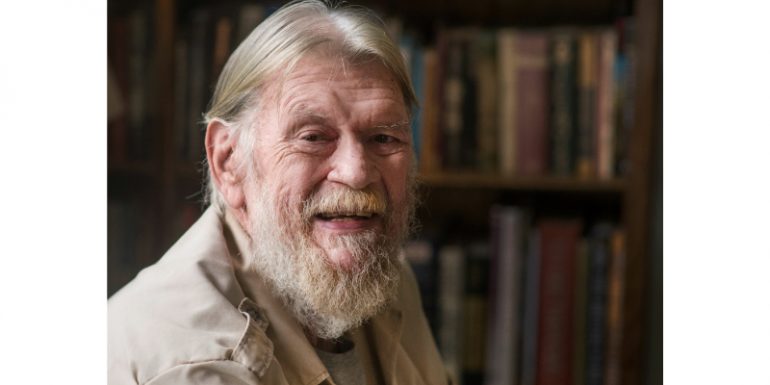

By Lisa Schmelz | Photography by Holly Leitner

Patrick Quinn is seated inside Speedo’s Harborside Pub & Grill in downtown Lake Geneva on a rainy Saturday morning. Just a few tables are occupied, and when a visitor enters, Quinn deftly makes introductions like he owns the place — only he doesn’t. Such is the beauty of Patrick Quinn. His ease with people, with place, with the past and present, make him one of those people you want to know.

“Let’s sit in the back,” he says after pleasantries are exchanged between the visitor and the regulars. “We can talk better there.”

A waitress brings coffee, but only the visitor orders breakfast. “I don’t eat breakfast,” explains Quinn. “I have coffee.”

There is more percolating in Quinn than caffeine. A retired archivist for Northwestern University, where he spent over 30 years preserving the history of the esteemed college, he’s also a published author whose curiosity hasn’t diminished over his 76 years. The keeper of Lake Geneva’s history, he’s a reliable source for historical inquiries of all stripes.

“I liked history from the time I was a young elementary student,” he says, his hands around his mug of just-freshened coffee. “I liked the idea of history.”

His weekly column in the Lake Geneva Regional News for the last eight years is lively, informative and helps us remember what is easy to forget. He also serves on the boards of the Lake Geneva Historic Preservation Commission, the Friends of the Geneva Theater, the Geneva Lake Museum and the Walworth County Genealogical Society.

Rob Ireland is the general manager and editor of the Lake Geneva Regional News. He says community columnists like Quinn are rare in that Quinn provides a perspective that is both well-sourced and personal. “He grew up in Lake Geneva, so he really knows the city probably better than anyone,” says Ireland. “He knows the history, and knows the people. He’s the definition of a local guy, and I mean that in the best possible way.”

A ROUGH BEGINNING

An only child, Patrick Quinn was born to Helen (Wardingle) and Bernard Quinn in 1942 at Lakeland Hospital in Elkhorn. After fighting in the Battle of the Bulge in World War II, his father returned home — but not for long. “He split,” explains Quinn. “And I was always told he died in a car crash down in Illinois.”

In 1945, Quinn lost his mother to pneumonia. Raised by his maternal grandparents, Thomas and Lillie Wilkinson, he thrived in local schools. His high school English teacher, Bruce Johnson, is 92 and can still summon memories of his time with Quinn.

“He and his buddies, they were harmless folks,” says Johnson. “They loved to play little tricks, but they were harmless. What can you ask of teenage males? I was a little surprised when I learned he was an archivist because those weren’t his inclinations in high school.”

Fortunately, time is expansive and allows us to develop into what others, or we ourselves, couldn’t see earlier. For Quinn, that meant graduating from Badger High School in 1960 and heading to the University of Wisconsin-Madison, where he earned a bachelor’s degree in English and then entered graduate school. But the civil rights movement and escalating war in Vietnam soon changed his focus.

LIVING HISTORY

“I dropped out of grad school … I borrowed some money and took a bus to Montgomery, Alabama,” he remembers. “I was in the civil rights movement in Selma and was almost killed three times. It was a very dangerous time with the Ku Klux Klan.”

Quinn was one of many who helped assemble the physical stage that civil rights leader, Martin Luther King Jr., would speak from following the historic march from Selma to Montgomery.

“The one thing I like to say is that I was the next speaker after Martin Luther King, but not as memorable,” he says.

So what were his words? “I told people where the buses were that they needed to get on.”

Not a dream-speech, but logistics matter in all movements.

When he returned to Wisconsin, he taught briefly at Racine Park High School. Then history knocked again. The father he thought “died in a car crash down in Illinois,” was alive and living in San Francisco. His father’s sister, Sister Mary Bernetta Quinn, a well-known Catholic nun and academic whose work in poetry analysis is still lauded, thought the younger Quinn had a right to know the truth.

“She wrote me a letter in April of ‘65,” Quinn recalls, “and as soon as I got it, I drove out to the Bay Area in California.”

FOLLOWING THE CLUES

Joining him on the journey were two friends, one of whom owned the Volvo that powered their search before search engines like Google made such things possible from your sofa.

“We drove non-stop,” he remembers. “We made it in 30 hours from Madison to San Francisco. We stopped only to go to the bathroom and pick up beer.”

Remarkably, Quinn found his father in just two weeks. “It was difficult,” he says. “I found police records all over the place and rooming house records.”

Those records eventually led Quinn to an Alcoholics Anonymous Clubhouse in Alameda, east of San Francisco. “I’d been all over the place, so I went there, to this AA club, and there was this guy polishing the counter there, or making coffee, and I asked him ‘Do you know Bernard Quinn?’ and he shook his head no and then he asked ‘Who wants to know?’ and I said ‘I’m his son.’ And he said ‘Barry doesn’t have a son.’”

Things then got a wee bit physical, Quinn adds, and in a matter of minutes, anonymity clearly out the window, he had his father’s phone number and was dialing from a pay phone. His father picked up after a couple of rings.

“He said ‘I’ll be there in five minutes.’ Five minutes later, he pulls up in an old Buick and we went to a bar to talk,” recounts Quinn of their first conversation. “He drank orange juice and I drank beer.”

He would learn that his father had struggled with alcohol for decades, even before the war, but eventually found sobriety.

“I got to know him, and we kept in touch,” he says.

Quinn’s father died three years later at a veteran’s hospital in Martinez, California. When he wasn’t able to bury him in a veteran’s cemetery, Quinn had his body brought to Lake Geneva. “I had him buried next to my mother,” he explains.

BUILDING A LIFE AND PRESERVING THE PAST

In 1965, Quinn married his first wife, Martha “Marty” Miller. In 1966, he began working for the Wisconsin State Historical Society and remained there until 1971. The Quinns welcomed two daughters, Abra and Rachel, and remained committed to a life of academia and social justice. In 1972, Quinn joined the Archives Department at UW-Madison and then in 1974 he began his career with the Archives Department at Northwestern University.

On his first day at Northwestern, there were just two, four-drawer filing cabinets of archived material. By the time he retired in 2008, the university archives featured nearly 1,000 collections of papers and records, and over 600,000 photographs and other artifacts.

By 1979, Quinn and Marty divorced, but remained on such good terms that he penned her obituary when she died in June 2018.

Retirement certainly hasn’t slowed Quinn down. Residing in the home he was raised in with his second wife, Mary (Janzen) Quinn, once the director of Public Programs at the Newberry Library in Chicago, he continues to vigorously remind us of the need to preserve the past. And when he publishes a new book, he makes his way over to his high school English teacher’s house.

“Every time he has a new book,” says Johnson, “he comes up meekly to my back door, I don’t have a front door, and he just comes up meekly, which is not Pat, and says, ‘I have this for you.’ He’s a good man. He’s a very stalwart, forward-thinking guy.”

Midwestern Muse and Other Poems is his most recent work, and was published by Red Dawn Press in 2014. Vivid, personal and accessible, the collection of poems describes the pursuit of the answers that link us all. “Unmarked Graves” is just 54 words, and was penned following Quinn’s search for his great-great-grandparents’ final resting place in St. Francis de Sales Cemetery in Lake Geneva. It seems the flat stone markers of William and Rose Quinn’s final resting places were buried by a century of sodden soil. So like he’s done for over 50 years, Quinn dug — literally dug — until he found an answer, and with it, a precious realization:

Unmarked Graves

I stood staring at the flat grassy plots

seeing nothing

astonished that there remained

no evidence

of the two lives that lay beneath me.

such an ignominious end

to a long journey

begun a century ago

an ocean across

But then the precious irony

came to mind:

It was I who was their stone.

Quinn knows, though, that the past always remains partly hidden. Revealed in fragments, we rarely get to piece it together completely. “You never figure everything out,” he says, “So I’m always still looking around for all kinds of stuff. You just keep looking.”