By Anne Morrissy | Photography by: Clint Farlinger, ©Chicago History Museum, and Lake Geneva Public Library

In a 1907 article in the Chicago Tribune, one of the paper’s fearless reporters purchased a ticket on the “Millionaire’s Special” — the extra train that Chicago’s wealthiest denizens used to escape the city to their Lake Geneva estates for the weekend — with the express purpose of adding up the accumulated wealth represented on the train. In the article, entitled “Forty Millionaires on One Train,” the writer estimates (conservatively) that the estates of the 40 or so men and women on the train represent approximately $200 million in 1907 money, or the equivalent of just under $5 billion today.

Amid the six parlor cars on the 90-minute trip to the Williams Bay station, the author spies almost all of the high-ranking Chicago luminaries with ties to the Lake Geneva area: Harry Selfridge sits with Charles Hutchinson and RT Crane; bankers John J. Mitchell and NW Harris chat nearby. Other men present include Allerton, Swift, Lytton, Bartlett, Wetherell and John M. Smyth. And among this constellation of Chicago’s wealthiest and most important men sits one man whose name will be forever immortalized in the topography of downtown Chicago when the river road is ceremoniously renamed for him: also riding the train is Chicago magnate Charles H. Wacker, en route to Fair Lawn, his summer estate.

EARLY LIFE IN CHICAGO

Charles H. Wacker was one of the great Chicago success stories of the late 19th and early 20th centuries, and one of few city magnates at that time to be born and raised in the city. The son of German immigrants who settled in the fledgling city when it was still very much a growing town in the shadow of St. Louis, Wacker was born in Chicago on August 29, 1856. Perhaps because of this, his passion for his home city would animate his work throughout his life. Like many children of German immigrants, Wacker valued education, first attending Lake Forest Academy and then traveling to Europe to study at universities in Stuttgart, Germany and Geneva, Switzerland. When he returned from Europe in 1880, he initially pursued trading and real estate before partnering with his father in the family malting firm, F. Wacker & Son.

Seemingly successful at everything he turned his attention to, Charles Wacker eventually assumed the presidency of the malting firm upon his father’s death in 1884 and went on to serve as president of the McAvoy Brewing Company, president and director of the Chicago Heights Land Association, director of the Corn Exchange National Bank, director of Chicago Title and Trust Company, president of the Chicago Heights Terminal Transfer Company, and several other enterprises over the course of his successful career.

THE CHICAGO PLAN COMMISSION

Although his business successes remained impressive throughout his life, it was Wacker’s civic work that would ultimately endear him to generations of Chicagoans and ensure his household-name status into the 21st century. In 1892, at the age of 35, he joined the directorate of the Chicago Columbian Exposition as the youngest director and a member of the Ways and Means Committee. The remarkable success of the World’s Fair catapulted Chicago into a new era of civic pride and inspired several decades of city projects intended to elevate the once swampy, unrefined reputation of Chicago. In 1907, under the direction of one of the city’s powerful social clubs, the Commercial Club, this trend of civic-minded improvement led to the formation of the earliest iteration of the Chicago Plan Commission.

The Commission’s goal was to establish a blueprint for the future development of Chicago. It was “the first comprehensive effort to discipline Chicago’s unruly growth,” explains historian Donald L. Miller in his book City of the Century: The Epic of Chicago and the Making of America.

In 1909, the Commission’s work culminated in the publishing of the 1909 Plan of Chicago by famed architect and urban planner Daniel K. Burnham, which Miller describes as “the greatest municipal project in Chicago’s history” and “the crowning achievement of an impressive succession of civic improvements begun during the ‘Columbian’ season.” Rather than limiting the scope of the Plan to the immediate downtown area, Burnham and the planners included aspirational, longrange plans that encompassed a 60-mile radius. They imagined a network of highways around the city, great forest preserves within easy access and an expansion of existing parks. Closer to downtown, they predicted a continuous parkway from Jackson Park to Winnetka, a monumental bridge across the Chicago River, broader traffic arteries, numerous diagonal streets, an imposing civic center and many other improvements.

Once the Plan was published, Chicago Mayor Fred A. Busse created a city partnership with the Commission and selected Charles Wacker to serve as the Plan Commission’s chairman. It was a significant honor for the civic-minded Wacker and a role he maintained until he was forced to step down due to poor health in 1927. Through his service to the Chicago Plan Commission, Wacker found an outlet for his passion to ensure that Chicago would one day be considered a world-class city.

During Wacker’s 18-year tenure as chairman of the Chicago Plan Commission, Chicagoans approved 86 Plan-related bond issues covering 17 different projects with a combined cost of $234 million. These projects helped to shape Chicago into the city we recognize today. Some of these included: the widening of 12th Street (Roosevelt Road); the widening and straightening of Michigan Avenue; the construction of the famous double-decker bridge over Michigan Avenue; the straightening of the South Branch of the Chicago River; the construction of Soldier Field, Northerly Island, Navy Pier, and Outer Lake Shore Drive; and the transformation of congested and dirty Market Street into an impressive double-decker (now triple-decker) road next to the river. So vital was Wacker’s work in ensuring that these projects were completed that the City decided to name this river road for him: Wacker Drive. Sadly, when the mayor officially opened Wacker Drive in 1926, Wacker himself was too ill to attend the ceremony.

FAIR LAWN

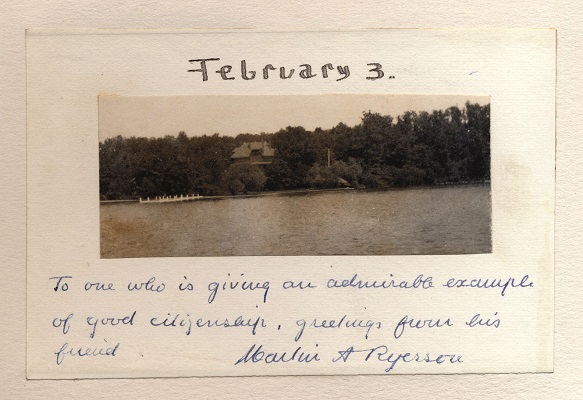

Despite his obvious love for Chicago, Wacker craved a country getaway, and in 1892, he and his wife Ottille “Tillie” Glade Wacker followed the lead of several of their Chicago friends and purchased 27 acres of land on the south shore of Geneva Lake. Because of his responsibilities with the World’s Columbian Exhibition in 1893, they spent that summer in a rented cottage with their two young boys (a daughter, Rosalie, would follow later in the decade) and waited until the close of the World’s Fair to begin construction of their Southern Colonial-inspired summer home, which they named “Fair Lawn.”

During Fair Lawn’s construction, Wacker turned his attention for detail and his indomitable energy to the project, boasting years later that he had personally inspected every foot of lumber and could say with certainty that there was not a single knot in the house. He supervised the building of the house, as well as the planting of several exotic trees on the property, including a Chinese Gingko tree, a Liquidambar and a Camperdown Elm. Several of the trees he planted were not suited to the Upper Midwestern climate, but Wacker’s passion for them (and his ability to hire top-notch staff and the star landscape designer Jens Jensen) ensured their survival for many years. The property also contained a white oak tree with an unusual bend in its trunk, which Wacker claimed was a “marker tree” used as a reference point by the Potawatomi Indians when they inhabited the area, and a tree known as the “Rosalie tree,” which Wacker planted the day his daughter was born.

In contrast to the exaggerated opulence displayed by some of the lake homes of the era, and despite the vast fortune of its owner, Fair Lawn was a relatively modest country home. It was set back from the lake to emphasize its rural setting, and visitors frequently described Fair Lawn as “comfortable,” “livable,” and “informal.” In keeping with its Southern Colonial style, the house contained a separate service wing which was connected by a latticed walkway. The main house featured three large rooms extending from a central foyer: a living room, a dining room and a billiard room. In addition to these, the house boasted a sizeable screen porch off the dining room that could also be used for meals, and a veranda overlooking the lake. The second and third floors were reserved for private areas including bedrooms and studies. In 1939, a reporter for the Chicago Tribune was particularly enamored of the dining room, which she described as “an unusually pleasant room with cushioned window seats around a bay that looks out upon a delightful vista of smooth lawn, trees and flower garden.” The walls and cabinets of that room were paneled in natural wood and finished with an amber stain that imparted a “rosy glow.”

The Wackers spent as much time as possible in Lake Geneva, often opening Fair Lawn at Easter and spending weekends in Lake Geneva through Thanksgiving. As with many families during this era, Tillie and the children would generally stay at the lake full-time during the summer, while Charles Wacker commuted on the Millionaires’ Special for the weekend. After Tillie’s death in 1904, he continued to bring the children to the lake in the summer, most likely in the care of a nanny.

During his time at the lake, Wacker tended to prefer leisure pursuits, joining the Lake Geneva Country Club and the Lake Geneva Yacht Club (where his son Frederick was an avid sailor), but he also participated in events to benefit the Holiday Home Camp, the Lake Geneva Horticultural Society and other local charities.

A FAMILY LEGACY

In March 1919, the 62-year-old Wacker married 34-year-old Ella Todtmann. Despite the decline of his health in the 1920s, they continued to spend as much time as possible at Fair Lawn. Three days after the great stock market crash, on Oct. 31, 1929, Charles Wacker passed away at Fair Lawn with his wife and two of his children by his side.

Ten years later, at the time of the Tribune reporter’s visit, Ella remained living in the house with Charles’ daughter Rosalie, Rosalie’s husband Earle Zimmerman and their children. Fair Lawn remained in the Wacker family through Ella’s death in 1969, until 1975, when the heirs sold the home for use as a guest house to their then-neighbors, Bill Bell and his wife Lee Phillip, Hollywood producers and creators of the soap operas “The Young & The Restless” (set in a fictionalized Genoa City, Wisconsin) and “The Bold & The Beautiful.”

Unlike many of the homes built on Geneva Lake in the 1890s, Fair Lawn is still standing, though it has changed hands since the days it served as a guest house for Hollywood visitors. (Wacker seems to have had more lasting taste than many of his contemporaries; one of his Victorian mansions in Chicago is still standing as well and just sold last July for just under $1.6 million.) Today, Fair Lawn’s continued presence on the lake serves as a quiet memorial to the man who, perhaps more than any other, shaped modern-day Chicago into the world-class city that it is today.