By Anne Morrissy | Photography by Shanna Wolf unless noted

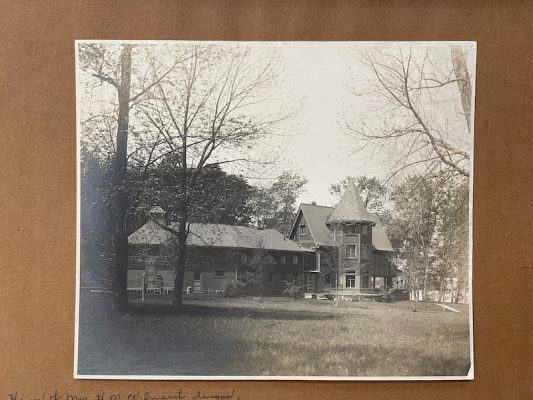

For many years, the historic turret room, where cartoonist Sidney Smith had once drawn his nationally famous Andy Gump comic strip, sat perfectly preserved on the lawn of his former estate on the south shore of Geneva Lake, waiting patiently for its second act. Glen Arden, the elegant, late Queen Anne-style home that Smith had purchased in 1922, dated to the late 19th century, its long, lake-facing open veranda recalling an era of women in straw hats and long, white dresses sipping iced tea on a hot summer day.

However, time had taken its toll on the beautiful house, and it was razed in 2004. Homeowners Allison and Michael Childers engaged architects McCormack + Etten, along with Maddock Construction, to undertake a process that is known as “historic reconstruction.” This is a process in which the original building is demolished, but key architectural details are salvaged and the original footprint and general layout of the home is used to construct a new home that looks nearly identical to the original from the outside.

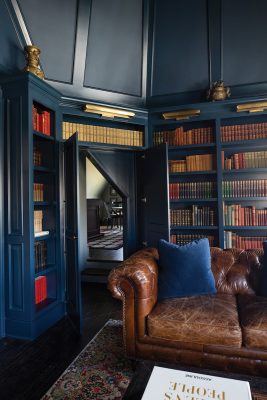

For the Childerses, one of the most important architectural features to preserve in its entirety was Glen Arden’s distinctive, top-floor turret. The family hired a renowned expert to detach and carefully lower the entire turret room to the ground — without a single book falling off the shelves! — where it remained for many years. That’s when the real research began.

Allison Childers had lived in the home since she was a child, and always felt a deep connection to it. By undertaking an historic reconstruction of her beloved childhood home, she also discovered a true passion for its architectural history, conducting research at the Chicago History Museum and the Art Institute of Chicago, and staying up late into the night to source period-appropriate details like millwork, hardware, stair elements and molding. The more she learned, the more enthralled she became.

MARY HAWES WILMARTH’S GLEN ARDEN

Glen Arden’s history is, indeed, fascinating. The original house was built in 1893 by a wealthy Chicago widow named Mary Hawes Wilmarth. In the fall of 1892, Wilmarth purchased 10 acres on the newly developing south shore from Arthur Kaye for $10,000, making it one of the priciest land purchases on the lake at that time. (She eventually acquired additional acreage and added 200 more feet of lake frontage to the property.)

To design a home where she and her daughter Anna could spend their summers, Wilmarth turned to a family friend, architect Dwight H. Perkins, who was at that time employed by the Chicago firm of Burnham & Root. Childers’ research indicates that this might be one of the first, if not the first, residential project Perkins ever designed. In 1894, with Burnham’s assistance, Perkins would strike out on his own and become well-known for his design of a large number of schools, large public parks and other public buildings in Chicago and its suburbs. He only designed a few residences, all in what became known as the “Prairie Style.”

The home that Perkins designed for Wilmarth combines elements of that style. But it also reveals the tastes of its owner, Wilmarth, who by all accounts was a strong-willed and decisive person. In an era in which women were expected to limit their interests to domestic life and philanthropy, Wilmarth was a true trailblazer. Born in 1837 in New Bedford, Massachusetts, Wilmarth was well educated and socially conscious. After marrying her husband Henry M. Wilmarth, a wealthy gas fixture manufacturer and founder of the First National Bank of Chicago, Mary Hawes Wilmarth moved to Chicago and became an active leader in the progressive social movements taking root there in the second half of the 19th century. Not long afterward, Wilmarth became a leading suffragist in Chicago, vigorously advocating for a woman’s right to vote. She also championed causes that aimed to feed, clothe and employ disadvantaged women, and educate their children. She served as the President of the Illinois branch of the Consumers League and supported the Legal Aid Society and the Women’s Trade Union League. At the age of 73, Wilmarth marched in the 1910 garment workers’ strike, and posted bond for those who were arrested. Wilmarth served as president of the exclusive women’s club, the Fortnightly of Chicago, and was an active member of the Chicago Women’s Club as well.

During this later period in Wilmarth’s life, one of her closest friends was Jane Addams, the internationally revered founder of Chicago’s progressive settlement house, Hull House. Wilmarth had been a strong financial supporter of Hull House from its founding in 1889, and even served as the first president of its Board of Trustees. After Wilmarth moved into her Lake Geneva summer home in 1893, her philanthropy and activism expanded to this area as well. She and daughter Anna spent the summer season in Lake Geneva and maintained an active social and philanthropic life here. She was an early member of the Lake Geneva Country Club and a strong supporter of Holiday Home Camp and the Lake Geneva Public Library, later sponsoring presentations on women’s suffrage for the Geneva Lake community. According to local Lake Geneva historian Chris Brookes, true to their convictions, Wilmarth and Anna also sponsored twice-yearly receptions at Glen Arden to honor and entertain the staff of the nearby estates. “Games, refreshments … even the yacht was available to all the workers,” Brookes explains in a video on the Wisconsin Historical Society website.

In September of 1911, Glen Arden served as the location of Anna’s wedding to Harold L. Ickes, a former Chicago journalist, attorney and active political reformer who would eventually go on to serve as the U.S. Secretary of the Interior under Franklin D. Roosevelt. The wedding, Anna’s second, was a small, private ceremony attended by “family and intimate friends” according to the Chicago Tribune, including Anna’s two children from her previous marriage, Wilmarth and Frances Thompson.

SIDNEY SMITH

Following her daughter’s marriage to Ickes, Mary Hawes Wilmarth continued to spend her summers on Geneva Lake until her death in 1919 at the age of 82. In her final days, Wilmarth sent for her good friend, Jane Addams, who arrived at Glen Arden in time to say her goodbyes. After Wilmarth’s death, Anna and Harold Ickes inherited the home, but their lives had become increasingly demanding — Anna would eventually be elected one of the first women to serve in the Illinois State Legislature, and the couple had added two more children to their family.

So in 1922, Anna and Harold Ickes opted to sell Glen Arden to the famous cartoonist Sidney Smith, whose popular comic strip, “The Gumps,” had debuted just five years earlier, and was carried by the newly formed Chicago Tribune New York News syndicate to reach a wide, national audience. The strip’s popularity was unlike anything that had come before it. “The Gumps” was one of the first comic strips to feature an ongoing storyline from week to week, and as a result, the characters, including beleaguered, bombastic patriarch Andy Gump, became beloved pop culture icons whose exploits were even adapted into animated film shorts and radio programs.

In 1922, riding the comic strip’s success, Smith signed a $1 million contract to continue drawing “The Gumps,” and that same year, he purchased Glen Arden, renaming it Trudehurst. Two years later, Smith hosted an over-the-top, tongue- in-cheek reception to unveil a life-size bronze statue of Andy Gump at the entrance of the estate, the progenitor of the Andy Gump statue that today resides in Lake Geneva’s Flat Iron Park. During his time at Trudehurst, Smith converted the turret room into his office and studio, where he drew each week’s installment of “The Gumps.” Childers points out that a large star painted on the turret’s wooden floor may have been a clever nod to Andy Gump’s profession: sheriff.

Smith owned Trudehurst until 1930, when he sold it to G.W. McKee of Rockford. Eventually, Childers’ parents purchased the home in the 1960s, by which time some of the surrounding 30 acres had been sold for development. Childers describes the home at that time as a “classic lake home from another era.”

REBUILDING HISTORY

When it came time to tackle the historic rebuilding of Glen Arden, the Childerses knew they wanted the exterior of the house to remain as similar to the original as possible, while updating the interior with modern amenities like an elevator, an expanded kitchen, a garage, additional bathrooms and energy efficient doors and windows. Although they would be modernizing the interior, it was imperative to Allison that the inside of the home feel authentic to the historic period of Glen Arden’s heyday in the late 1800s and early 1900s, including the obligatory squeak in the stair!

In order to ensure that Glen Arden retained a strong sense of character, Allison selected different ornate crown molding for each room, as well as different tile patterns for each bathroom. She commissioned the reproduction of the original French-style casement windows, and for the grand staircase, she chose a repeating pattern of intricately hand- turned balusters installed in groups of three. The white oak floors throughout the kitchen, living and dining area were custom-milled from old-growth trees felled on the property — Michael proudly points out that the knots and slight imperfections tell the history of the tree. In the Butler’s Pantry off the dining room, some of Glen Arden’s original leaded windows were repurposed as cabinet doors. “You wouldn’t guess it, but the Butler’s Pantry is one of everyone’s favorite rooms,” says Allison.

Other salvaged parts of the original house include some of the newel posts (now repurposed as legs on the kitchen island), a handrailing to the basement and a pedestal sink in the third-floor powder room. In order to maintain the historic look of the home and make the incredible lake views the focal point of each room, modern conveniences like TVs, a surround sound system and some of the kitchen appliances have been cleverly hidden in architectural details or faced with vintage-style cabinetry. “The best compliment is when someone walks in and says they can’t believe this is a new house,” Allison explains.

But the showstopper of the historic reconstruction of Glen Arden is the turret room, now back in its place of honor atop the house. Allison explains that getting the original room back in place was a labor of love that required a complicated permitting process. Because of the height of the roof and finial on top of the turret, the Childerses and their architects had to submit a code variance request to the town and county that necessitated written support from local residents. They set up a website to update the community supporters on the rebuilding process and to share the estate’s history. “It truly was a community effort all the way through,” Allison explains.

All of the hard work was worth it. “The day the crane operator arrived to lift the turret back into place, the Lady of the Lake halted its tour out in front of the house so everyone could watch it being reattached,” she says.

Today, people walking the Shore Path between Linn Pier Road and Buttons Bay might never guess that Glen Arden had ever been demolished, and this is exactly the effect that Allison and Michael Childers hoped to accomplish when they set out on this project. Admiring the results of their hard work, Allison explains they are thrilled with the new chapter in Glen Arden’s history. She says, “We believe that when you live in a house as historic and special as this one, you do not own it; you are its stewards.”