By Anne Morrissy | Historic Images Courtesy Lake Geneva Public Library

On August 14, 1948, special investigators burst into the Cavern Bar, located in the basement of the Hotel Geneva in Lake Geneva, and announced a raid. An earlier raid the previous week had failed to turn up evidence of a rumored betting operation at the Cavern Bar; that day, all the betting equipment had been moved out before investigators arrived. They suspected that the hotel’s co-owner, Hobart Hermansen, had been tipped off. But on their second try, the investigators found more than 50 people engaged in illegal horse-race gambling, or “betting on the book.” Hermansen was the only one arrested that day, but he was quickly released and fined around $800. The hotel and bar remained open throughout the legal proceedings. It almost had to. In 1948, the Hotel Geneva was the most famous hotel in Lake Geneva, and had been for more than 30 years.

A NEW HOTEL FOR A NEW ERA

The Hotel Geneva began its life as the Lake Geneva Hotel, and had been a point of community pride from its earliest days. In 1911, two entrepreneurial businessmen visiting the area, Arthur L. Richards and John J. Williams, looked at the vacant lot where the grand Whiting House Hotel had once stood (the site of the current Geneva Towers Condominiums), and hatched a business plan. The Whiting House had burned down in 1894, but plans to build a new hotel had stalled. Richards and Williams recognized a huge opportunity in the empty lot, so they formed the Lake Geneva Hotel Company to sell stock subscriptions in a new hotel venture. Several Lake Geneva summer residents, tycoons of Chicago banking and business, helped to fund the project.

Richards and Williams envisioned an unparalleled year-round resort to rival the famous Tuxedo Club of Tuxedo Park, New York. An editorial in the Lake Geneva Regional News extolled the new hotel plan, enthusing that “beauty of design was the first thing considered.” To ensure that their new hotel was sufficiently beautiful, modern and memorable for visitors, Richards and Williams decided to hire an internationally famous architect with Wisconsin roots: Frank Lloyd Wright.

FRANK LLOYD WRIGHT AND LAKE GENEVA

The year 1911 was a time of great change for Wright. The previous year, he had left his Oak Park studio, abandoning his wife and children, and departed for a year in Europe with his mistress. Upon his return, he began building a new home and studio for himself in Spring Green, Wisconsin, which he would call Taliesin. The commission for the Lake Geneva Hotel came at a time when he needed to shore up his social reputation and earn more money to pay off his debts. Although he had designed five private residences and a yacht club on nearby Delavan Lake a decade earlier, the hotel was the first commission Wright received on Geneva Lake, and in fact it would remain the only Wright-designed building on the lake. Wright’s design for the hotel was a resounding application of his groundbreaking architectural philosophies, a low, horizontal building intended to blend into the natural environment.

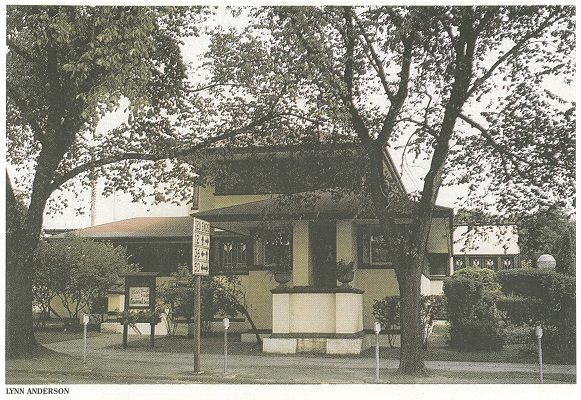

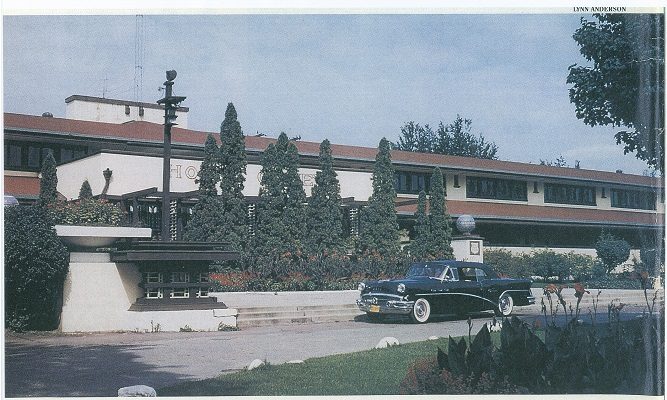

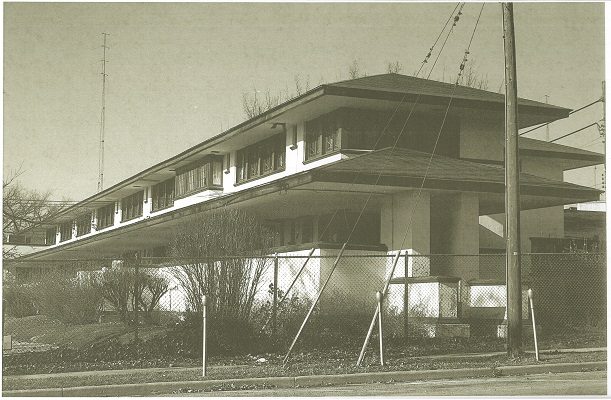

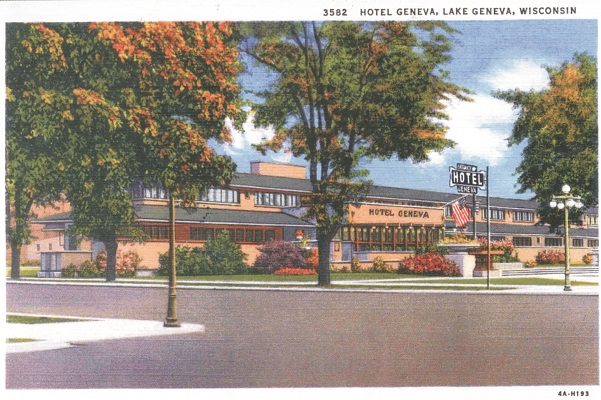

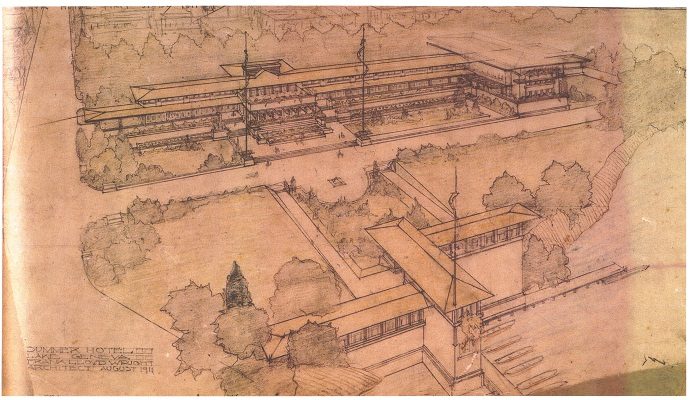

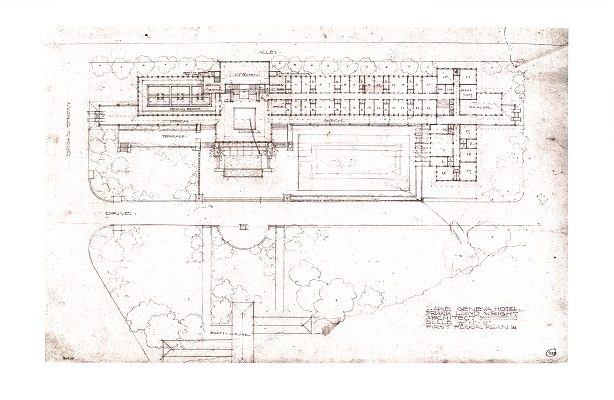

To achieve this, Wright designed the Lake Geneva Hotel as a two-story structure filling the entire block between Broad and Center streets, with the front of the hotel facing the lagoon that flows into the White River. As designed by Wright, the hotel boasted 360 feet of water frontage with a wide, shaded piazza running the length of its front. Although stylistically, the hotel presaged the famous Imperial Hotel Wright would design in Tokyo a few years later, the Lake Geneva Hotel is credited by some architectural historians as the prototype for a new kind of lodging that would proliferate in America a few decades later: the two-story motor hotel.

Construction began in May of 1912 and the hotel opened just three months later with 30 of its 70 total guest rooms ready for occupancy. The formal opening took place a month after that with a grand dinner in the new dining room. According to newspaper accounts at the time, the interior was finished in light fumed oak and American gum-wood, and decorated in shades of green and brown. The ceilings in the lobby and dining room featured ornate art-glass skylights, which complemented the leaded “Tulip”-style windows for which Wright is now well known. A massive brick fireplace, one of Wright’s hallmarks, dominated the lobby. Custom-designed sconces and light fixtures throughout the hotel operated on electricity, the newest technology of the era.

Because Richards and Williams envisioned the hotel as a year-round resort, a large coal burning boiler room took up a significant part of the basement, and each room boasted its own radiator heat. Additionally, a great majority of the rooms came with private baths. (The hotel was connected to the new sewer system that the city of Lake Geneva installed to accommodate its construction.) For the era, Frank Lloyd Wright’s Lake Geneva Hotel was cutting-edge and top of the line.

The grand opening of the Lake Geneva Hotel, along with its excellent fine-dining restaurant helmed by a French chef, drew lake residents as well as a sizable faction of tourists to Lake Geneva. Shortly after its opening, the Lake Geneva Regional News marveled that during the opening week over 100 “auto machines” were parked in front of the building. Over the next few years, the hotel proved a popular tourist stop, but the building itself presented challenges and was costly to maintain. In the 1930s, the Depression hit the hotel business particularly hard. As a result, ownership and management of the hotel changed hands several times in its first three decades.

THE HERMANSEN HEYDAY

Around 1940, Lake Como innkeeper Christian Hermansen bought the Lake Geneva Hotel (more commonly known by this time as the “Hotel Geneva”) and placed it under the management of his son, Harry, with help from brothers Hobart and Inar. The Hermansens had earned a certain notoriety in the area: during Prohibition, their Como Inn housed a well-trafficked speakeasy called The Sewer, which was rumored to have hosted some of Chicago’s most infamous gangsters of the era. (Lending some credence to these rumors, in 1932 Hobart Hermansen married Lucille Moran, ex-wife of famous Chicago gangster George “Bugs” Moran.) The Hermansen family would go on to own the Hotel Geneva for the next 25 years.

Harry’s son, retired Hilton Hotels & Resorts Vice President Allen C. Hermansen, remembers working there in the 1940s, while he was a student at Lake Geneva High School. “I worked there every summer, because the hotel was strictly summer-only at that point,” he remembers. “The heating costs in the winter were just too high to keep it open. Every summer I did a little bit of anything that needed to be done.” Allen says that his uncle Hobart recruited seasonal employees from a similar winter resort in Hot Springs, Arkansas. “He hired the chef, the bell captain and the maître’d and told them they could bring their own staff with them,” he explains. “They were impressively good at their jobs. I will never forget the sight of one man in his white jacket coming out of the kitchen with a flourish, one fully loaded tray up in the air and another fully loaded tray down here …” — indicating hip height — “It was quite a sight to behold.”

SLOT MACHINES, PONY RIDES AND A SPECIAL VISITOR

According to Allen, his uncle Hobart — known in the local papers as the “SlotMachine King of Walworth County” — managed an underground casino in the basement of the Hotel Geneva. This casino was the target of the 1948 raid, though federal investigators failed to uncover the full operation. (Local stories of tunnels dug from the basement of the Hotel Geneva to the basements of neighboring buildings for the purpose of rum-running during Prohibition may explain how Hobart Hermansen was able to remove the betting equipment without being detected.) “It was mostly an accepted thing back then,” Allen explains. “You just paid a little money here and there to the right people and they’d let you keep running [the casino.]”

Not all of the activities at the Hotel Geneva during this time had to take place underground, however. The restaurant and bar proved popular with both tourists and locals. Brochures from the era advertised a wide range of entertainment available to hotel guests: swimming, dancing, golfing, boating, fishing, tennis, riding. Allen remembers that his father made an arrangement with a local stable to keep a few horses and ponies on the north side of the property. Guests could mount their rides at the Hotel Geneva and then follow a guide through downtown Lake Geneva, out to riding trails on Sheridan Springs Road. Children could take pony rides around Flat Iron Park. “I led the ponies one summer,” Allen remembers with a laugh. Occasionally, he says his uncle Hobart would put sugar cubes in his pocket and entice a particularly tiny Shetland pony to follow him into the lobby of the hotel, much to the delight of the children staying there.

Following Harry Hermansen’s death in the 1950s, Hobart took a larger role in the management of the hotel. One day in 1957, he gave a tour of the property to a very special visitor: Frank Lloyd Wright himself. The venerated architect was back in the area as a guest of Philip K. Wrigley and his wife. After touring the hotel he had designed 46 years earlier, Wright reportedly said that it seemed to be in good condition, and if he were designing it again, he would “make few changes.”

A LANDMARK LOST TO CHANGING TASTES

By the 1960s, the Hotel Geneva faced increasing competition from new resorts like The Abbey in Fontana. Frank Lloyd Wright’s architecture looked heavy and old-fashioned by comparison to the new, lighter mid-century style. The building remained costly to maintain and business had dropped. The Hermansens decided to sell the Hotel Geneva to a group of investors that included State Assemblyman George Borg and Majestic Hills Ski Area owner Bill Grunow. Borg and Grunow added a glassed-in swimming pool in front of the building, reconfigured the lobby to include a piano bar and changed the name to the Geneva Inn, hoping to reposition the property as a modern motor hotel.

However, in 1969, Borg and Grunow sold the property again, this time to a Kenosha businessman with plans to raze the building. Some of the interior was salvaged — the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee received more than 100 panes of leaded art glass windows from the hotel, some of which are on long-term loan to the Lake Geneva Public Library. The Geneva Lake Museum also has a few window panes, as well as some of the Wright-designed wall sconces that once graced the hotel’s walls. But over the winter of 19691970, the once-great, Frank Lloyd Wright-designed Hotel Geneva was reduced to a pile of rubble.

Williams Bay resident Tom Palmersheim remembers frequenting the Hotel Geneva and speaks for many local residents of the era when he describes the feeling of loss. “It was a different feeling walking into the place,” he says. “It was very sad to see it get torn down. There was an aura about it. When you walked in the front door, it was like you walked into a completely different world.”