By Sarah T. Lahey

Editor’s Note: This is a sequel to an article that appeared in the fall 2017 issue of At The Lake, in which Sarah Lahey introduced us to some of the influential Chicago families who lived along the shores of Geneva Lake in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Here she explores three more families.

To discover the early history of Chicago — the titans of industry who built the city, the founders of its institutions — one need look no further than Geneva Lake. Nearly all of the visionary founders of Chicago built summer homes on the shores of Geneva Lake after the Great Chicago Fire. The history of these lakeside homes and their owners reveals a group of legendary families who shaped not only the future of Chicago but also the culture of Lake Geneva.

ADOLPHUS AND ABBEY BARTLETT

Adolphus Clay Bartlett would eventually own a mansion on Geneva Lake, but he started out as the son of a sawmill operator. Bartlett was born in 1844 to very humble means, and was raised by a widow. His mother managed to send him to school, however, until the age of 18 — later than most of his friends.

At age 19, Bartlett took his first job in Chicago as a clerk in a hardware store. He was in charge of stocking shelves and writing orders. He always arrived early and stayed late. Six years later, he was named a general partner in the business.

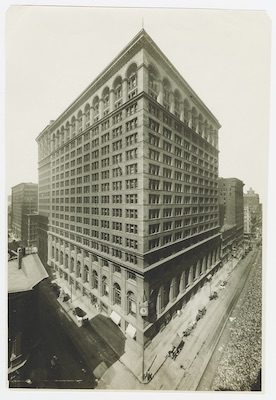

Following the Great Chicago Fire of 1871, increased demand for hardware supplies created a boom in business. Bartlett’s store soon incorporated under the name of Hibbard, Spencer, Bartlett & Company, and they opened a 10-story warehouse next to the State Street Bridge. By 1914, Bartlett was the only surviving partner of the firm, making him president of one of the largest hardware firms in the world.

Adding to this success, Bartlett introduced a new line of hand tools in 1932 called “True Value.” This brand skyrocketed, earning $30 million in annual sales by 1948. The name, True Value, survives today as a chain of successful hardware stores.

Outside of work, Bartlett was uncomfortable with fancy parties and social gatherings. He preferred reading books at home. He married young, to a woman named Mary Pitkin, who died 13 years later. She left him a widower with four young children. Bartlett then married Abbey Hitchcock, 18 years his junior and a graduate of the University of Michigan. This young sparkplug kept Bartlett on his toes and gave him a fifth child to round out the family. It was Abbey who moved with Bartlett to Lake Geneva, where the couple enjoyed a summer home from 1906-1922.

On Geneva Lake, Bartlett built the well-known House in the Woods on the north shore over the course of 19051906. The contractor, Richard Souter, was busy building the home of Norman Wait Harris (now Glanworth Gardens — The Richard H. Driehaus estate), so arrangements had to be made to finish the house over the winter. Bartlett was determined to have his house completed by the spring of 1906 as a surprise birthday present to Abbey.

So, like any good contractor, Mr. Souter borrowed a three-ring circus tent from P.T. Barnum, who lodged his operations in Delavan during the off-season. The tent was placed around the construction site and heated over the winter. Architect Howard Van Dorn Shaw had a tough time working under such conditions, but — as Barnum would have said — the show must go on.

Upon completion of House in the Woods, Bartlett’s son, Frederick C. Bartlett, painted murals throughout the home. It later was featured in the June 1909 issue of Ladies Home Journal. The editor described the “summer cottage” as strongly Italian in character, full of “Old World touches cleverly adapted to a new environment.”

When he wasn’t relaxing in Wisconsin, Bartlett led an extremely active life in Chicago. Besides running the hardware business, he was a director at the First National Bank, Northern Trust Company, Chicago Relief Society and Art Institute. He also was a member of the Chicago Board of Education and a trustee of Beloit College.

He made his name, however, as a patron of the University of Chicago, where he became a director in 1906. Bartlett funded construction of the Frank Bartlett Gymnasium, now used as a dining hall, in honor of his eldest son who died of appendicitis.

At the dedication ceremony, Bartlett reportedly said: “This gymnasium was built, not by the death of Frank Bartlett, but through his life.” The same might be said of Bartlett himself, whom we remember for the accomplishments of his ambitious life.

MARTIN AND CARRIE RYERSON

To the west of House in the Woods was the Lake Geneva estate of Martin A. Ryerson, a fellow benefactor of the University of Chicago.

Ryerson was a long-time Lake Geneva resident (1898-1932), an art lover and a man of considerable means. He grew up in Chicago, where his father ran a lumber business that became an overnight success. The Great Chicago Fire destroyed all of the city’s major lumberyards — except Ryerson Lumber.

A Midwesterner at heart, Ryerson’s father tried not to spoil his children. The young Ryerson attended Chicago public schools for most of his life, and only later studied in Paris and Switzerland. Adding to his accomplishments, Ryerson graduated from Harvard Law School in 1878. By age 25, he was practicing law and married to Carrie Hutchinson, a local Chicago girl.

Things changed when Ryerson’s father died suddenly. Ryerson went from being a lawyer to being the richest man in Chicago. He was only 34 years old. Ryerson had several choices: he could retire, keep up the lumber business or pursue his passions. He decided on the latter: supporting art and education in the city of Chicago.

As the University of Chicago writes, Ryerson was “one of the most important civic leaders in the first half century of the University’s history.” He was an original founder, recruiting world-class faculty and overseeing the architectural design of campus. He also served on the Board of Trustees for 30 years (1892-1922).

One of his most significant gifts to the university was $350,000 for the construction of the Ryerson Physics Laboratory, which still operates today. His eye for rare books and manuscripts also helped to establish the university’s library. With additional funds, he created an endowed professorship for faculty members with outstanding achievements in public service. On the whole, his contributions to the University of Chicago are un-measurable.

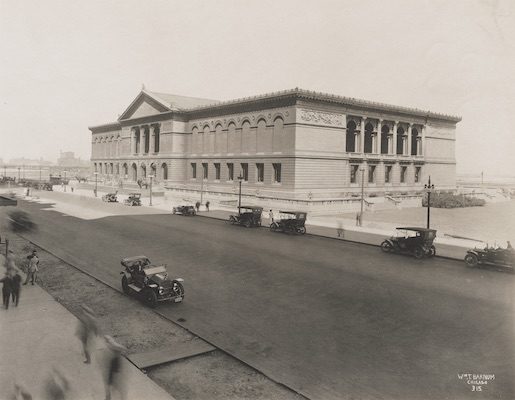

Ryerson’s other great passion was the Art Institute of Chicago. He was a trustee of the Institute for over 40 years, serving on the board until the year he died. Ryerson had an amazing eye for fine art and became one of the museum’s most important collectors. Along with his Lake Geneva neighbor, Charles L. Hutchinson (a cousin to his wife), Ryerson traveled the world and made bold acquisitions.

He was an early supporter of the movement called “impressionism,” which was still emerging in the 1890s. Ryerson became personal friends with Claude Monet, who visited him at his home in Lake Geneva. When Ryerson died, his personal collection went to the Art Institute, including five paintings by Renoir, 16 by Monet, and others by Rembrandt, Cézanne and Gauguin.

These priceless works are now major attractions in the Impressionist Wing.

In Ryerson’s free time, he served as vice president of the Field Museum of Natural History, and sat on the Board of Directors at the Rockefeller Foundation, Chicago Orphan Asylum, Northern Trust Bank and Corn Exchange National Bank.

Lake Geneva offered him a much-needed chance to relax. Ryerson discovered the lake during a trip to see Yerkes Observatory, originally built by the University of Chicago. He immediately fell in love with the area and bought Bonnie Brae, an estate on the lake’s north shore. The Ryersons tripled the property size upon purchase, creating a vast retreat of 98 acres and 1,250 feet of lake frontage. At one point, 34 people lived on the property to care for the estate.

At the lake, Ryerson enjoyed his steam yacht, Hathor, and golfed with Hutchinson at Lake Geneva Country Club. He also was a member of the Lake Geneva Yacht Club, where a trophy is still named in his honor. The Ryersons had no children, so they enjoyed Lake Geneva’s social life.

Ryerson died in his lakeside home in 1932, at the age of 75. Upon his death, his entire estate was dissolved. He and his wife, Carrie, agreed that one-tenth of the estate would go to her and the rest to charity. In all, Ryerson left $6 million (equivalent to nearly $100 million today) to be divided equally among the Art Institute, Field Museum, and University of Chicago. Ryerson was a generous man, and we find his greatest legacy in the museums, libraries and universities that he founded.

SAMUEL AND AGNES ALLERTON

Samuel W. Allerton lived on the same stretch of Geneva Lake, along Snake Road, as Ryerson and Bartlett, but he did not entirely fit with their crowd. Allerton liked to trade cattle, not play golf.

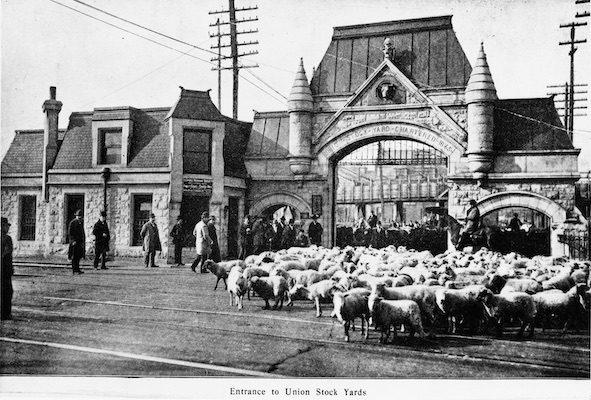

He was famous for founding Chicago’s Union Stockyards, the largest centralized market for livestock in U.S. history. He also co-founded the First National Bank of Chicago, created to process his livestock transactions. In 1893, biographer John Flinn described him as “one of Chicago’s best known citizens.” Allerton owned homes in Chicago, Lake Geneva and Pasadena, California. Still, his heart was always on the Illinois prairie, where he owned more than 40,000 acres of farmland.

As a child, Allerton offered to work for local farmers. By age 21, he had accumulated enough capital to invest in a cattle ranch in Piatt County, Illinois. In 1856, he relocated to Chicago, where he managed to corner the hog market after prices plummeted. This proved a shrewd move. A decade later, Allerton founded the Union Stock Yards, which A. Waterman credits with doing more for the “commercial advancement of Chicago than any other enterprise.”

Allerton had an equally gifted vision for transportation, bringing the first ever cable car system to Chicago. He also ran for mayor in 1893. Although he lost the race, Allerton continued to be a civic leader, founding the St. Charles Home for Boys.

On a personal level, Allerton faced some difficult times. His first wife, Paduella, died when their youngest child was only seven years old. In mourning, Allerton married Paduella’s sister, Agnes, with whom he spent the rest of his life. Agnes moved to Lake Geneva with him in 1884 and made Wisconsin their summer home.

The Allertons purchased the Forest Lodge estate, which was originally a bachelor’s fishing lodge. Agnes called the purchase “sheer folly,” and the name stuck. The Folly, designed by architect Henry Lord Gay, rested on 26 acres of land at Manning’s Point, located at the northern tip of the narrows.

As described in 1908, the Folly showcased “a velvet lawn in front, and a superb garden, greenhouses, barns and dairy in the rear.” Indeed, green space was a priority for “Farmer Allerton,” as he was affectionately known. Allerton never became much of a socialite and apparently liked to tuck his napkin under his chin, “where it belongs.” As historians Ann Wolfmeyer and Mary Gage noted, “Despite their substantial wealth, the Allertons preferred to remain ‘just folks.’”

Agnes Allerton put her practical skills to good use in supporting Lake Geneva’s Woods School, which served Irish immigrants in the early 20th century. Every summer, when parents were busy working at the lake’s mansions, children were left unattended. Agnes established a summer program at Woods School to teach these students life skills such as sewing, cooking and housekeeping. She purchased the equipment herself and taught some of the classes. In her will, Agnes left every item of furniture from the Folly estate to Lake Geneva’s Holiday Home, a charity camp established in 1887 to provide an outdoor retreat for urban children.

PERSONAL WEALTH LEADS TO PHILANTHROPIC EFFORTS

These legends of Lake Geneva are not fanciful figures, but real people. They were leaders in commerce and trailblazers in philanthropic pursuits. Certainly, these men and women enjoyed great privilege, but they converted their success into great purpose. Bartlett’s enormous generosity to the University of Chicago still provides students with a dining hall and meeting center. Ryerson’s relentless search for art survives in the Art Institute’s most popular gallery. Allerton’s stockyards, although now defunct, shaped the development of Chicago’s entire trading industry. These legendary couples shaped the world we live in, and they were neighbors at the lake.