By Tasha Downing | Photography by Holly Leitner and Wisconsin School for the Deaf

On a normal school day, a visitor to the Wisconsin School for the Deaf (WSD) in Delavan might find a group of children preparing to dive into art projects, or a group of teens clad in red-and-white Firebirds attire milling about the school’s historic halls. As the only school in the state of Wisconsin dedicated specifically to deaf education, the residential school operates under the direction of the Wisconsin Department of Public Instruction and enrolls an average of about 100 students each year (though the COVID pandemic has periodically interrupted in-person learning and led to slightly reduced enrollment). Students at WSD range in age from 3 to 21, and most of them live on campus Monday through Friday during the school year. Students of WSD enjoy the freedom of learning in a typical classroom environment, created and optimized especially for them.

Today, there are around 100 residential or day schools for the deaf and hard of hearing across the country. But until the widespread establishment of these schools, members of the deaf community in the United States lived largely in isolation, unaware that there were so many others who shared the same struggle to learn and to communicate. Barbara Hart grew up on the WSD campus, and both of her parents worked for the school. In an interview recorded in 2012, Hart explained that her mother, Selma Hart, became deaf at the age of 3 due to typhoid and scarlet fever. She described the lack of awareness surrounding deafness in the early 20th century. “My grandmother thought [that my mother] was the only deaf person in the world, because she had never seen or heard of a deaf person before,” recalled Hart. By happenstance, a stranger informed Hart’s grandmother about WSD, and Selma was sent there to attend school at the age of 9, remaining through high school graduation and going on to work at the school as an adult.

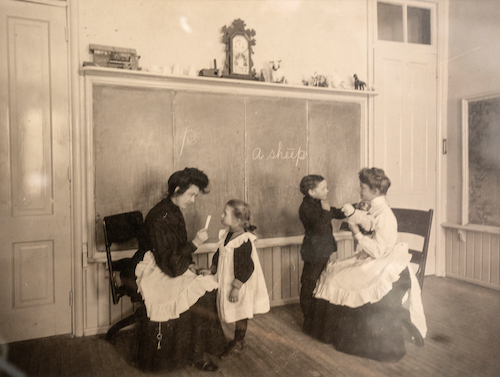

Hart’s grandmother’s confusion was not unusual, though schools dedicated to the education of deaf and hard-of-hearing students in the United States had been in existence since the early 1800s. In 1817, the first such school in the country opened in Hartford, Connecticut — today it is the American School for the Deaf (ASD). Thomas Hopkins Gallaudet, a Yale graduate and minister from Pennsylvania, became inspired by a chance meeting with a young deaf girl, and traveled to Europe to learn more about deaf education. There he met Laurent Clerc, a deaf instructor at the groundbreaking National Institute for Deaf Children in Paris. The two men returned to Connecticut and founded ASD, advancing the course of history for America’s deaf population. Both men would go on to leave an indelible mark on deaf education in the United States. Gallaudet’s son, Edward Miner (E.M.) Gallaudet, opened the first deaf school of higher learning, Gallaudet University, in Washington, D.C., and the majority of today’s modern American Sign Language (ASL) evolved from Clerc’s teachings.

Thanks to the work of these two men, institutional progress addressing the longstanding educational needs of the deaf flourished in the middle of the 19th century. Between 1817 and Clerc’s death in 1869, more than 30 specialized schools opened in the U.S., including one in the small town of Delavan, Wisconsin. The school’s presence in Delavan is a credit to the dedication and persistence of one pioneer farming family, the Chesebros. Ebenezer Chesebro moved from New York state to a farm near the newly formed town of Delavan in 1839, bringing with him his wife and children, including his daughter Ariadna, who was deaf and had previously attended the New York Institute for the Deaf and Dumb.

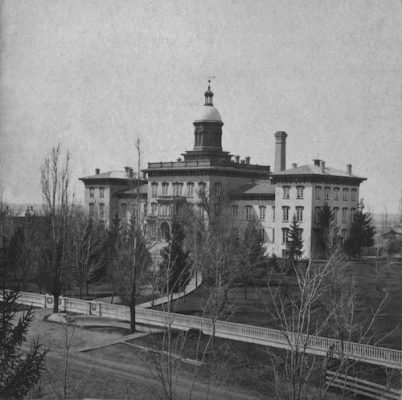

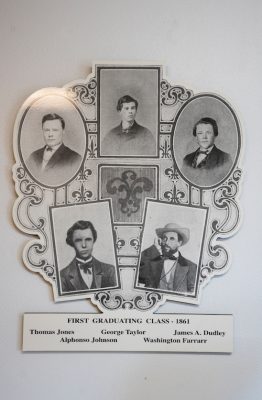

“[The area] was of course very rural when Ebenezer first arrived,” says Nell Fleming, current WSD librarian and archivist. “It was a wilderness, which appealed to the original families looking to establish a brand-new community based on their values: temperance and anti-slavery sentiments.” To continue Ariadna’s education, the Chesebros hired a series of tutors, who initially taught not only their daughter and a neighboring child who was hard of hearing, but also six other deaf or hard-of-hearing students. Recognizing a need for a deaf school in the area, in 1852, the Chesebro family enlisted the help of a local state assemblyman to petition the relatively new Wisconsin state legislature to establish a school for the deaf. With the Legislature’s approval, WSD was founded on April 19, 1852, on a parcel of 12 acres of land west of downtown Delavan donated by Franklin K. Phoenix, son of Delavan co-founder Samuel Phoenix, and a good friend of the Chesebros. Today, Ariadna Princess Chesebro is known as “the face that launched WSD.”

During its earliest years, the school persevered through incredible obstacles: some of the earliest deaf pupils had to travel as many as 40 miles to campus over poor roads to receive their education; in 1858, shortly after its founding, a diphtheria epidemic swept through Delavan’s population and claimed many lives, including the school’s beloved Ariadna; and in 1879, the school’s newly constructed main building burned down just 12 years after its completion. Despite these challenges, the school continued to grow its reputation as a respected and progressive institution with the admittance of its first African-American student in 1887, and a prestigious visit from E.M. Gallaudet for its 50th anniversary celebration in 1902.

Set against a lush, wooded landscape just west of Delavan’s historic downtown, the school once grew much of its own food through the cultivation of onsite gardens and a campus farm. An entry from WSD student Earl Hinterthuer’s journal dated May, 1915, described the idyllic setting: “The school is surrounded by a pond, forest trees and a creek on the top of the Institution Hill called ‘Phoenix Green.’” He went on to list 11 buildings on campus at that time, including classroom buildings, boys’ and girls’ dormitories, a boys’ gymnasium and a barn and cold storage building. Today, most of these buildings have been replaced by modern ones, though the campus still evokes an idyllic rural impression upon first arrival.

For today’s WSD students, Huff Hall serves as a home-away-from-home. Students travel from all across Wisconsin to attend the school, and many of them live on the school’s residential campus Monday through Friday. The Student Life staff of residential advisors encourages students to take on responsibilities and learn independence while supporting and encouraging them in their schoolwork and extracurricular activities. In addition to the residential and academic buildings, students have access to the Cordano Track and Field, baseball diamonds, tennis courts and playgrounds to ensure opportunities for physical activity and social engagement.

For the students and their families, the school often becomes a part of their lives beyond graduation. Casey Kelly works for WSD as an information technology and digital media specialist. He not only graduated from WSD but represents the fourth generation in his family to have attended the school. “I have three kids. The oldest two can hear, and the last child is deaf,” he explains. “He is eighth- generation deaf in our family.” Kelly’s great-grandmother, Ethel Cass Kelly, was the first member of the family to attend WSD, graduating in 1928.

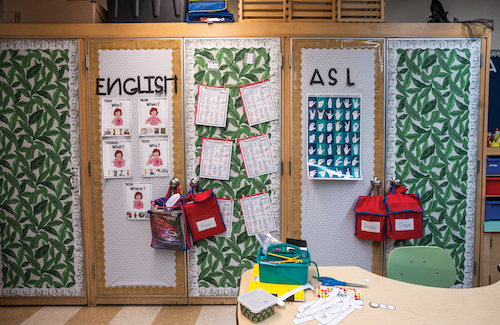

Kelly first entered the school at age 3, and says that the bonds formed as a student last a lifetime. He maintains a close friendship with a classmate he met during his first year there. Both Kelly’s parents (married for 44 years) and his grandparents (who were married for 62 years) met at WSD. “School gives us that language access and allows for wider communication opportunities,” Kelly explains. “At school, we learn the foundations of academic American Sign Language… [which] is monumental for students.” Kelly says that all of the school staff at WSD, whether deaf or hearing, are all exceptional role models who are deeply committed to deaf education, and deliver not only a mastery of academics but also set a positive example for students to pursue continuing and higher education.

According to Kelly, deaf and hard- of-hearing students in a traditional, mainstreamed school setting don’t always have access to the full variety of incidental learning that hearing children do. “As a hearing child, you can overhear things in the hallway outside of your academic conversation that teach you things, but as a deaf student you often rely on the interpreter to learn,” he says. By attending WSD, students have access to a full array of academic, social and extracurricular opportunities to enhance their learning.

During his time as a student, Kelly enjoyed playing for the WSD football team and competed in track and field. He says that activities like homecoming games and tournaments for various sports are a big deal for students, and the rivalries between WSD and other schools in their division are very competitive. Plus, these events provide an opportunity to engage with hearing peers over a shared activity. “Most of us really cared about the meets and games, hanging out with the other kids, meeting new kids. Being rivals but still coming together and socializing.” In addition to sporting events and academic competitions, WSD students are encouraged to take field trips and walk to downtown Delavan in their free time. According to Kelly, this independence and organic interaction is all part of the learning process.

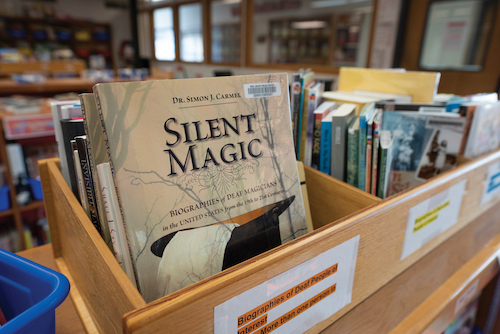

To further augment the academic experience, WSD is part of the Wisconsin Educational Services Program for the Deaf and Hard of Hearing (WESP-DHH) and works closely with deaf organizations in Wisconsin, like the Southern Lakes Association of the Deaf, to raise money and provide resources for community-building events. The WSD campus is also home to another major resource for the deaf and hard-of-hearing community — the Delavan campus houses the only library for the deaf in the state of Wisconsin. The materials in the WESP-DHH Educational Resource Library have been assembled specifically for Wisconsin residents who are deaf, hard of hearing or deafblind, and also for their families, students and professionals. “The library was built to be a central place of meeting in our school,” says Fleming.

“It has historically been a place where students and staff enjoy coming together to share and enhance the learning experience.”

This April, the Wisconsin School for the Deaf will celebrate 170 years of existence in Delavan, and it remains a paragon of deaf education in Wisconsin. As the school’s modern promotional materials explain, WSD remains forever committed to “preparing students to achieve their maximum potential and become successful citizens of the future.” As the tools, methods and activities continue to evolve with each new generation, the school remains, as ever, an extraordinary learning space and an environment designed to help the state’s deaf community thrive.